Engineered Microbes: The Organisms Powering Modern Biotech Through Fully Functional Recombinant DNA

Engineered Microbes: The Organisms Powering Modern Biotech Through Fully Functional Recombinant DNA

From life-saving vaccines to sustainable biofuels, a remarkable class of organisms now serve as living factories—engineered to carry fully functional recombinant DNA with precision and efficiency. These microorganisms, genetically modified to express foreign genes, have revolutionized biotechnology, enabling rapid advancements across medicine, agriculture, and industry. At the heart of this transformation lies recombinant DNA technology, where segments of genetic material from different species are combined into a host organism with perfect functionality, turning cells into precision-based biomanufacturers.

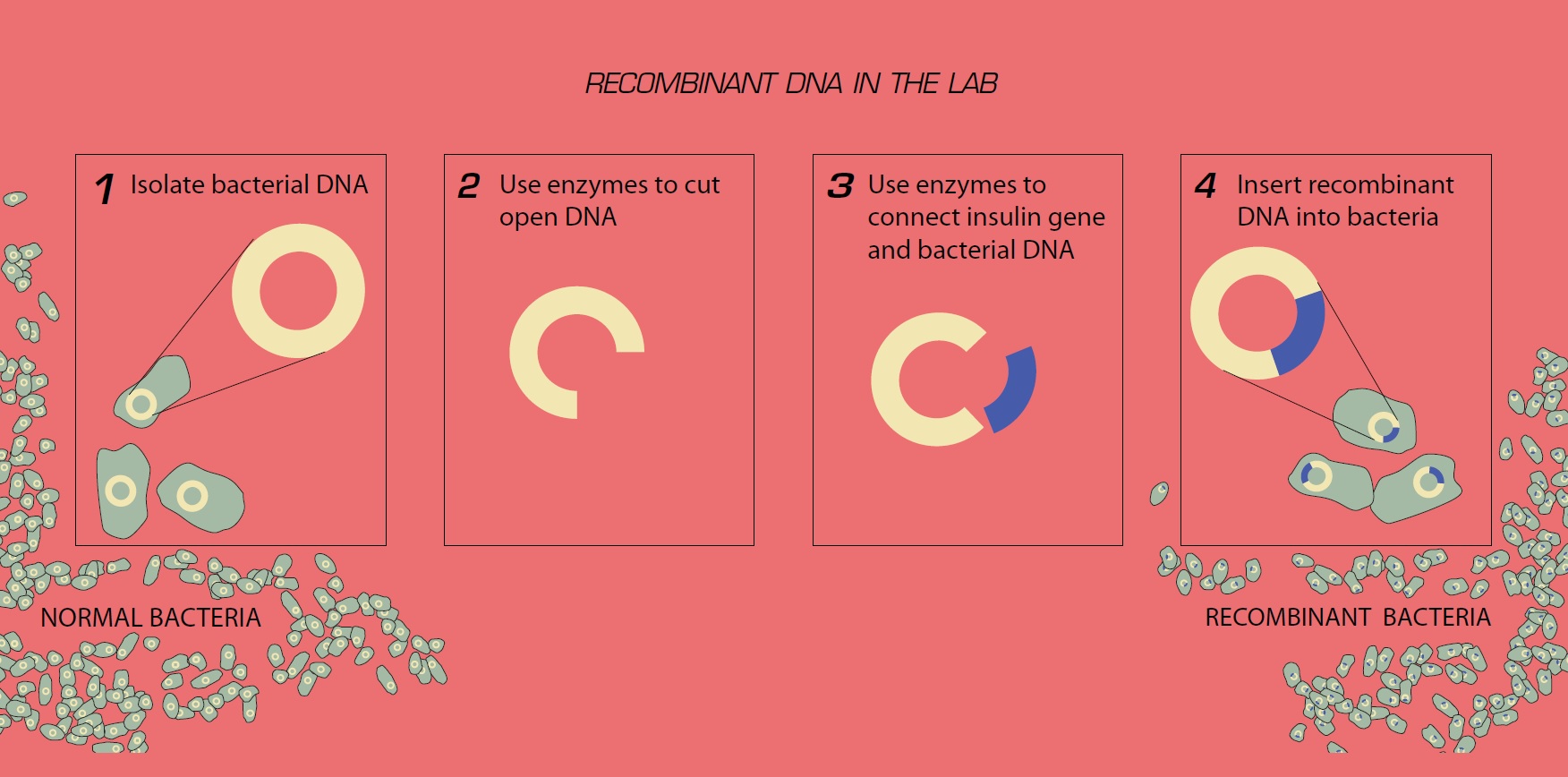

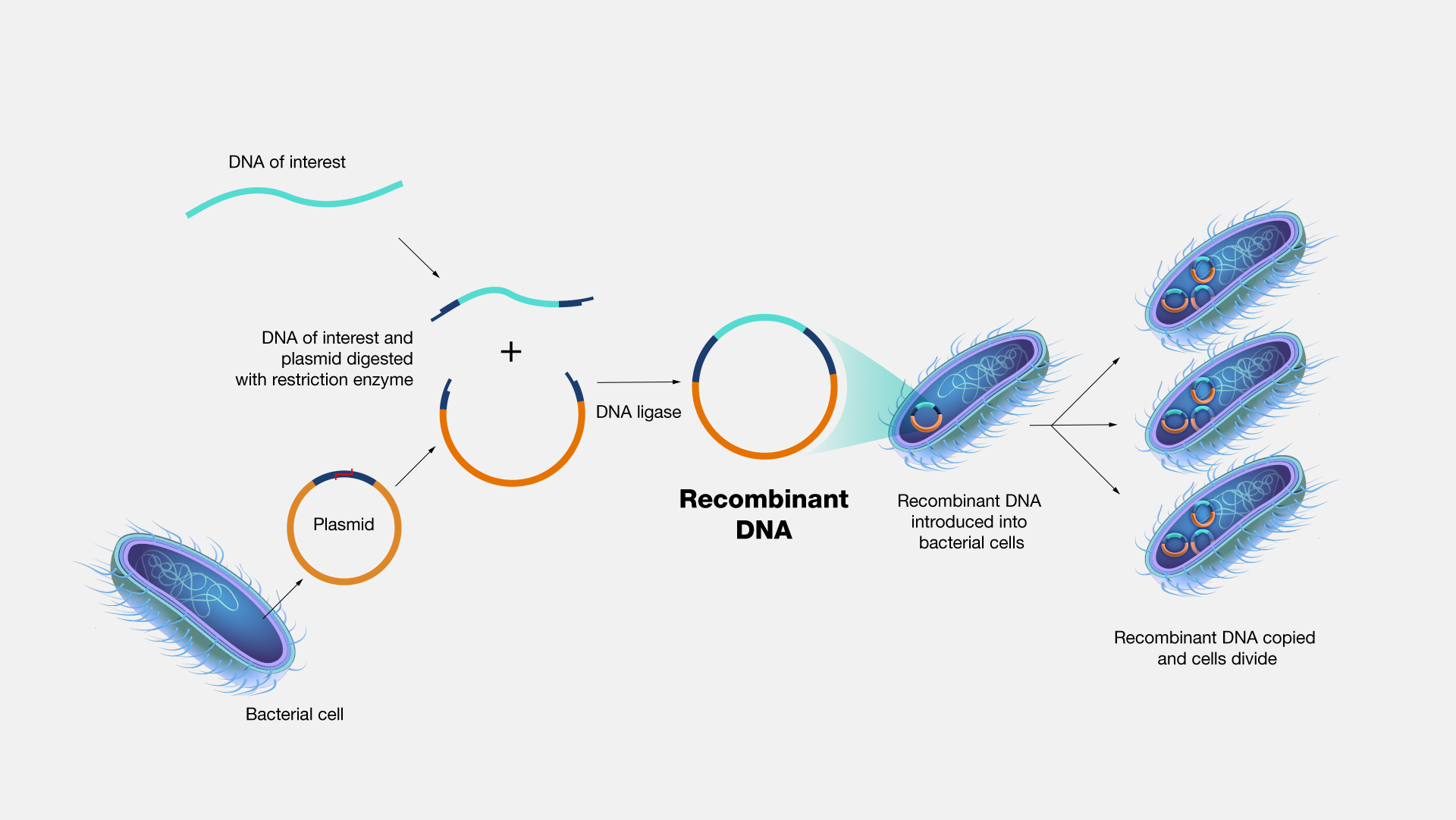

Recombinant DNA technology involves inserting a gene of interest—such as insulin-producing sequences or pest-resistance markers—into the genome of a host organism, ensuring that the new genetic code is not only present but fully active and expressed. The organism itself does not merely carry the DNA; it becomes a dynamic system that transcribes, translates, and utilizes this artificial blueprint to produce essential proteins or metabolic outputs. Among the most prominent players are Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and certain plant cell lines—each selected for their robustness, rapid replication, and proven compatibility with genetic manipulation.

One of the most studied organisms is Escherichia coli (E.

coli), a bacterium ubiquitous in laboratory settings due to its well-mapped genetics and ease of transformation. When outfitted with recombinant DNA, E. coli rapidly expresses desired proteins, making it the workhorse of recombinant protein production.

In the 1970s, scientists first demonstrated that engineered strains could produce human insulin by inserting the insulin gene into bacterial plasmids—ushering in a new era of diabetes treatment. “E. coli is not just a host; it’s a microfactory codified with synthetic biology,” notes Dr.

Lena Petrova, a synthetic biologist at MIT. “Its ability to swiftly multiply and produce complex proteins under controlled conditions is unmatched among natural lab organisms.”

Recombinant Leather and Biofabrication: Beyond Pharmaceuticals

While E. coli remains central in therapeutic protein production, other organisms have expanded the scope of recombinant DNA applications dramatically.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, commonly known as baker’s yeast, has emerged as a key eukaryotic platform. Unlike bacteria, yeast possesses a eukaryotic cellular machinery capable of performing post-translational modifications—such as glycosylation—critical for producing functional human proteins. This functional fidelity makes yeast indispensable in manufacturing monoclonal antibodies, vaccines, and enzymes for diagnostics.

More recently, scientists have used recombinant DNA to reprogram plant cells—not in soil, but in controlled bioreactors.

For example, tobacco and lettuce cells engineered with customized DNA sequences now produce antiviral compounds and industrial enzymes at scale. “We’ve turned plant cells into biofoundries—turning sunlight and carbon dioxide into a production platform,” explains Dr. Kenji Tanaka of the Biofabrication Institute.

“With functional recombinant DNA, these cells bridge biology and sustainability, offering scalable, eco-friendly manufacturing.”

Mechanisms Enabling Functional Expression

For recombinant DNA to function fully within an organism, several biological criteria must be met. The inserted gene must be properly positioned within the host genome or a stable plasmid, regulated by potent promoters that ensure high-level expression. Enhancers, terminators, and intra-organismic splicing mechanisms fine-tune the process, while codon optimization—adapting the foreign gene’s nucleotide sequence to match the host’s preferred coding rhythm—maximizes protein yield.

Researchers use advanced tools such as CRISPR-Cas9 and Gibson Assembly to insert and validate recombinant sequences efficiently.

“It’s not enough to just stick DNA in; the system must understand and execute it,” warns Dr. Amara Nkosi, a molecular engineer at SynBio Dynamics. “Functional DNA means the organism not only stores but correctly processes the genetic instructions—producing proteins at therapeutic or industrial levels without error.”

Fields like medicine have embraced this precision: recombinant DNA-engineered microbes now produce vaccines (e.g., hepatitis B surface antigen in yeast), cancer therapeutics, and gene therapies.

In agriculture, crops have been transformed to express insecticidal proteins or drought resistance genes through stable recombination. Industrial microbiology uses these organisms to ferment biofuels, bioplastics, and sustainable chemicals, reducing reliance on fossil fuels.

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

Despite rapid progress, deploying organisms with functional recombinant DNA presents complex challenges. Ensuring genetic stability over generations, preventing horizontal gene transfer to wild populations, and biosafety monitoring remain critical.Ethical discourse centers on responsible innovation—balancing breakthroughs in human health and environmental sustainability with ecological responsibility.

Regulatory frameworks, such as those developed by the FDA and WHO, have evolved to oversee recombinant DNA applications, emphasizing transparency and risk assessment. “Science moves fast, but public trust depends on accountability,” asserts Dr. Laurel Chen, a bioethicist at Stanford.

“Every engineered organism must be rigorously tested not only for efficacy but also for its containment and long-term impact.”

Emerging frontiers include synthetic cells and gene-drive systems, where recombinant DNA functions extend into programmable biology and ecosystem engineering. Yet for now, the most powerful organisms remain those already in use: bacteria, yeast, and plants—engineered not just to survive, but to produce, protect, and transform at molecular scales.

In essence, organisms harboring fully functional recombinant DNA stand at the frontier of biotechnological evolution—living vessels through which genes gain life, purpose, and global impact. From eradicating disease to redefining sustainable manufacturing, their engineered genomes redefine what biology can achieve.

This is technology not just applied to nature, but fused with it, unlocking possibilities once confined to science fiction. As research accelerates, these recombined life forms continue to push the boundaries of possibility—one gene at a time.

Related Post

Supercopa 2019 Final: Atlético Madrid's Triumph Over Real Madrid

Sportacus Reveals the Unseen Rise of Endurance Sports: From Tradition to Trend

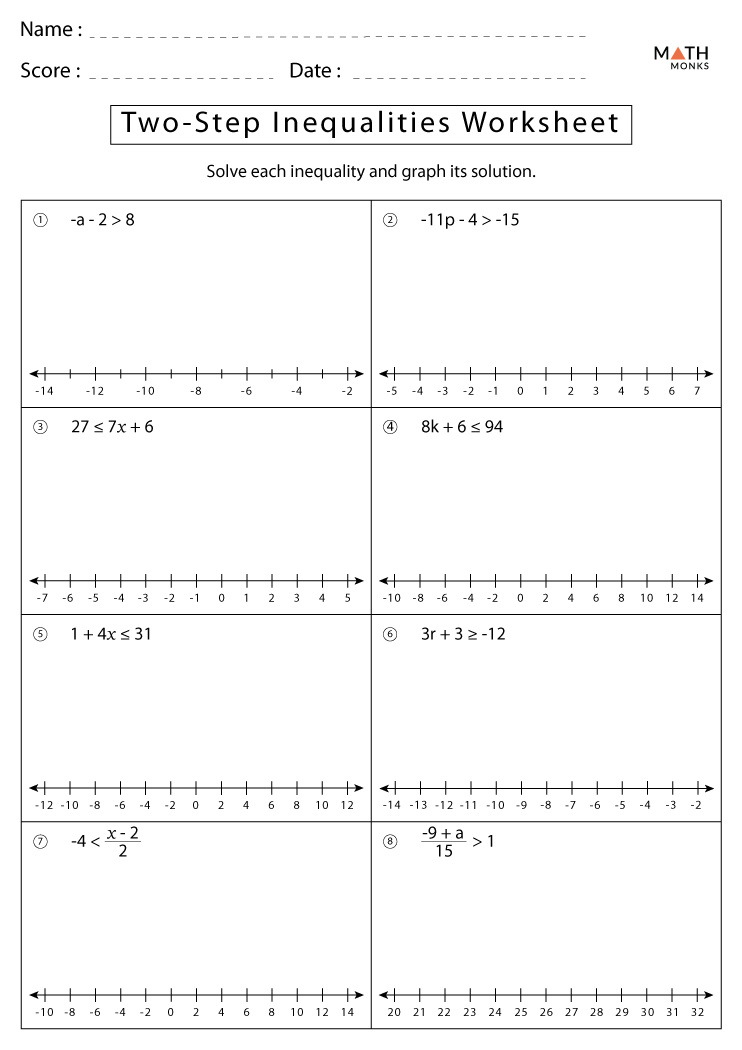

Master Two-Step Inequalities: The Step-by-Step Guide From Lesson 7.2 That Empowers Real-World Problem Solving

Mcdvoice Com Survey Billions in Receipts: How AI-Driven Feedback is Rewriting Customer Experience Standards