Endosymbiotic Theory: How Mitochondria and Chloroplasts Rewrote Earth’s Cellular History

Endosymbiotic Theory: How Mitochondria and Chloroplasts Rewrote Earth’s Cellular History

Every complex eukaryotic cell harbors tiny factories within its cytoplasm—mitochondria and chloroplasts—organelles whose origins defy the simplicity of modern biology. These structures, essential for energy production and photosynthesis, are now widely accepted to have arisen not through inherited design, but via a profound evolutionary merger: the endosymbiotic theory. Backed by robust genetic, biochemical, and structural evidence, this theory explains how free-living prokaryotes became permanent hosts inside ancestral cells over a billion years ago.

The convergence of multiple scientific disciplines—from molecular genetics to comparative genomics—has solidified this framework as the cornerstone of modern evolutionary biology.

The Genesis of an Revolutionary Idea

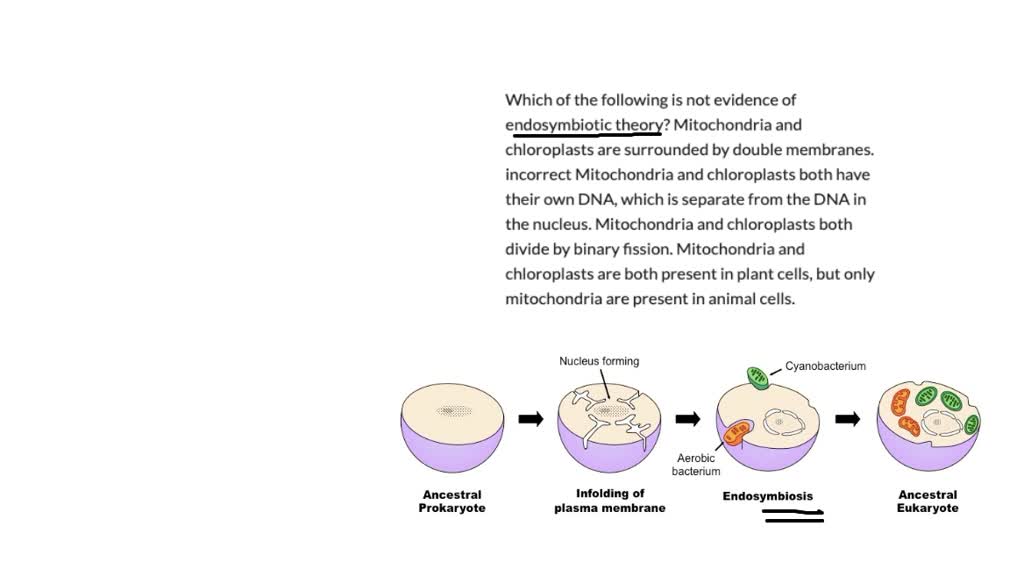

First proposed in the 1960s by biologist Lynn Margulis, the endosymbiotic theory challenged the long-held assumption that eukaryotic organelles evolved solely through internal cellular processes. At its core lies a deceptively simple but powerful premise: cyanobacteria once lived independently, were engulfed by a primitive archaeal cell, and evolved into chloroplasts; similarly, aerobic bacteria became mitochondria through internalization.What once seemed speculative is now bolstered by decades of scrutiny. Margulis documented how the parallels between organelles and bacteria—such as independent replication, unique DNA, and double-membrane architecture—point toward a shared evolutionary origin rather than convergence. “The idea that mitochondria and chloroplasts originated as free-living bacteria is no longer debated; it is the narrative woven from diverse and convergent lines of evidence.” — Lynn Margulis, evolutionary biologist This paradigm shift shifted the focus from static cellular compartments to dynamic evolutionary partnerships, redefining how scientists view cellular complexity.

Today, the theory is not just accepted—it is foundational to understanding eukaryotic diversification.

One of the most compelling lines of evidence lies in the genetic blueprint shared between organelles and prokaryotes. Mitochondria and chloroplasts each contain their own double-stranded DNA—distinct from the nuclear DNA in the host cell’s nucleus.

These organelle genomes resemble bacterial sequences in size, gene content, and even structural organization. For instance, mitochondrial DNA mirrors that of alphaprotobacteria, particularly the Rickettsiales group, while chloroplast DNA aligns closely with cyanobacterial genomes. This genomic similarity reflects a deep evolutionary heritage, with core genes involved in energy metabolism preserved directly from ancestral bacteria.

Moreover, these organelle genomes encode proteins critical for essential functions, many of which have no functional equivalents in the host nucleus.For example, mitochondrial DNA still produces subunits of cytochrome c oxidase—central to the electron transport chain—genes that operate autonomously within the organelle. This functional retention supports the idea that these structures were not merely invaginations of plasma membranes but living cells in their own right, capable of independent metabolism long before they were fully integrated into the host.

Biochemical and Structural Resemblances

Beyond genetics, biochemical pathways within mitochondria and chloroplasts reveal a bacterial signature.Both organelles rely on ribosomes nearly identical to those in prokaryotes—specifically, 70S ribosomes, unlike the 80S ribosomes found in eukaryotic cytosol. These ribosomes synthesize organelle-specific proteins without nuclear intermediates, reinforcing their prokaryotic ancestry. Additionally, their membrane systems—double lipid bilayers surrounding protein complexes—mirror the structure of bacterial membranes, a stark contrast to the membrane organization in eukaryotic organelles derived through other pathways.

The division of bioenergetic work is striking: mitochondria rotate molecular rotors in ATP synthase, enzymes directly derived from alphaproteobacterial ancestors, powering cellular energy. Chloroplasts employ a similar enzymatic machinery—centrosomes and ATP synthase variants—with cyanobacterial homologs, underscoring a direct lineage. These biochemical continuities create a seamless thread from ancient prokaryotes to modern eukaryotes.

The conservation extends to replication mechanisms. Mitochondria divide via binary fission, closely resembling bacterial reproduction, though regulated by host cell signals. They rotate midcell, a motility pattern observed in swimming proteobacteria.

Chloroplasts mirror cyanobacterial cell division cycles, suggesting their evolution retained ancestral replication strategies. These mechanisms, preserved across billions of years, highlight adaptive retention rather than convergent evolution.

Division of Labor: From Symbionts to Symbionts

An essential pillar of endosymbiotic theory is the transition from independent prokaryotes to integrated organelles. Early in eukaryotic evolution, a host cell—likely an archaeon—engaged in an endosymbiotic relationship with a bacterium.Evidence suggests this began with facultative association: the bacterium conferred metabolic advantages, such as aerobic respiration via mitochondria, enabling the host to exploit new ecological niches. Over time, genomic reduction stripped both partners of redundant functions, with critical genes transferred to host nuclear DNA. This interdependence transformed transient symbiosis into a permanent dependency.

Today, many mitochondrial and chloroplast proteins are encoded in the nucleus, transported into organelles, and essential for their function. This gene transfer—documented via comparative genomics—represents a molecular signature of evolutionary integration. The host cell no longer relies solely on its organelles; it governs their activity, illustrating a symbiotic partnership refined over eons.

Structural studies further illuminate this integration. Mitochondria and chloroplasts are enclosed in double membranes—an inside-out signature of engulfment. In some protists, morphological analysis reveals ongoing divide-and-recycle cycles, reminiscent of free-living bacteria adapting to host environments.

These observations affirm that while organelles have become indispensable, their evolutionary roots remain visible in every division, replication, and metabolic process.

Distinguishing Endosymbiosis from Competing Hypotheses

While the endosymbiotic theory stands dominant, it contrasts sharply with alternative proposals like the outcome hypothesis—where mitochondria originated from an intermediate host–bacterium fusion—and the multi-endosymbiotic hypothesis, which posits sequential engulfments giving rise to complex plastids in plants. Crucially, endosymbiosis is distinguished by irreplaceable evidence: consistent bacterial DNA, functional prokaryotic ribosomes, genomic gene transfer, and biochemical parallels. Other models fail to account for this full suite of data.The convergence of genomics, biochemistry, and cell biology makes endosymbiosis the most parsimonious explanation for organelle origins.

In recent years, even the timing and mechanics of these events have come into sharper focus. Phylogenetic trees show mitochondria predating complex eukaryotes, suggesting a deep historical root.

Meanwhile, CRISPR-based lineage tracing in model organisms provides experimental windows into ancient partnerships. Though direct fossil evidence of endosymbiosis eludes us, molecular clocks and comparative biology reconstruct a plausible timeline spanning over 1.5 billion years.

The Enduring Legacy of Symbiosis in Cellular Evolution

The endosymbiotic theory reshapes our understanding of life’s complexity—not as a linear progression, but as a dynamic interplay of competition, cooperation, and convergence.Mitochondria and chloroplasts are more than just organelles; they are living archives of evolutionary transformation, teaching us that survival often arises not from isolation, but from symbiosis. As research continues—leveraging advances in genomics and synthetic biology—this theory remains not only relevant, but vital. It reminds us that our own cellular existence is the legacy of ancient mergers, symbiotic partners turned indispensable.

In the quiet machinery of every eukaryotic cell, a story of transformation pulses—rooted in the past, unfolding in the present, and shaping the future of life on Earth.

Related Post

Here Is The Real Meaning Behind Erome Creator 19: Unveiling the Vision, Functions, and Cultural Impact of a Revolutionary Digital Platform

Is La Times A Reliable Source? Here’s What the Facts Reveal

Cambio De Aceite Y Filtros: Precios, Consejos y Todo Lo Que Necesitas Saber

Florida Man July 3rd: A Week of Bizarre Shenanigans and Unanswered Questions