Does Osmosis Require ATP? The Hidden Mechanism Behind Passive Water Movement

Does Osmosis Require ATP? The Hidden Mechanism Behind Passive Water Movement

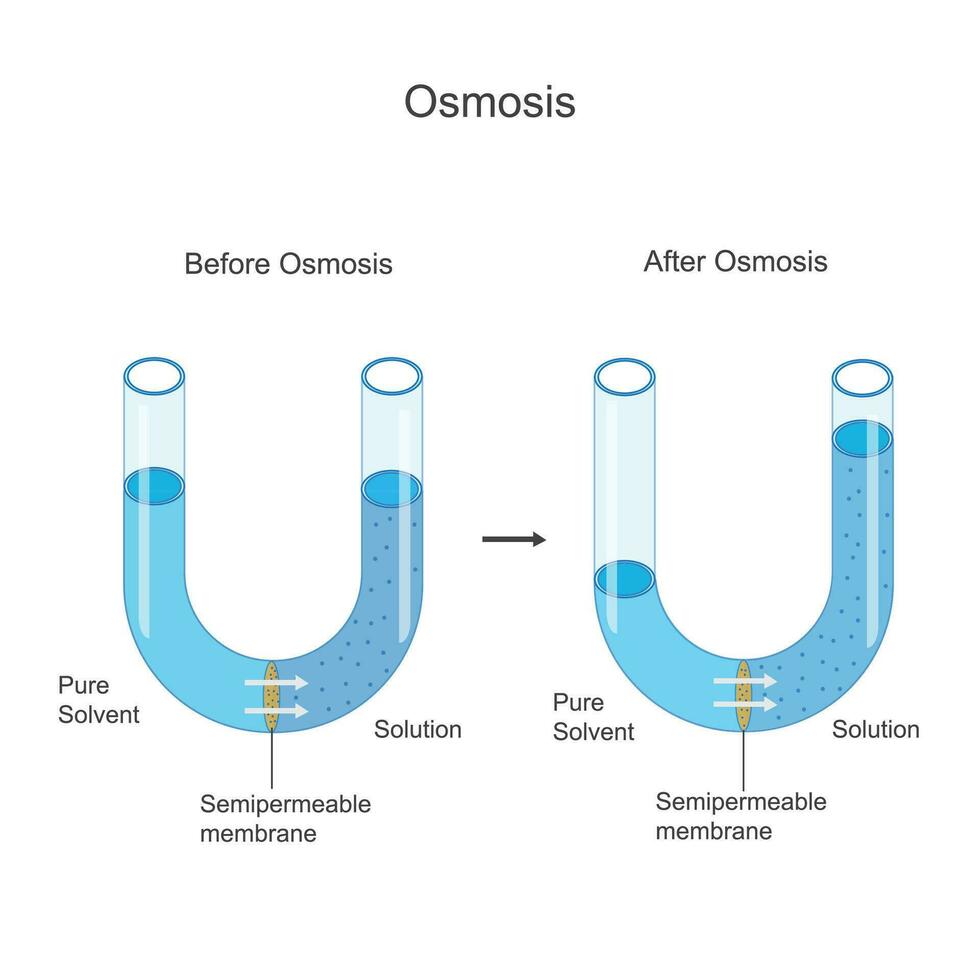

Osmosis, the fundamental process by which water crosses semipermeable membranes in response to solute concentration gradients, is often misunderstood as an energy-dependent process—yet the scientific truth reveals otherwise. Contrary to common assumptions, osmosis does not rely on ATP; it is a passive, concentration-driven phenomenon that requires no direct energy input. This revelation challenges intuitive perceptions of cellular fluid regulation and underscores the elegance of biological design.

As experts clarify, “Osmosis is the silent force in cells—no energy needed, only gradients,” says Dr. Elena Rostova, molecular biologist at the Institute for Cell Biophysics. ### The Physics of Passive Diffusion: Water’s Natural Tendency Osmosis occurs when Wasser molecules move across a selectively permeable membrane from a region of lower solute concentration (and higher water concentration) to a region of higher solute concentration (lower water concentration).

This movement is driven entirely by differences in water potential, not by ATP. Unlike active transport mechanisms that consume energy to move molecules against gradients, osmosis proceeds spontaneously as water seeks equilibrium. “Passive transport systems like aquaporins facilitate the rate of water movement but do not power it,” explains Dr.

Rostova. “The process obeys thermodynamic principles—water flows to balance free energy, not at a cost.” Water molecules continuously collide with and pass through membrane channels, but in the presence of solutes, their net movement cancels out until equilibrium is reached—no synthesis or hydrolysis required. This passive flow underscores why ATP is absent from the osmosis equation: the process taps directly into the natural kinetic energy already present in the system.

How ATP Comes Into Play — and Where It Doesn’t

Energy Debunked: The ATP Myths of Osmosis

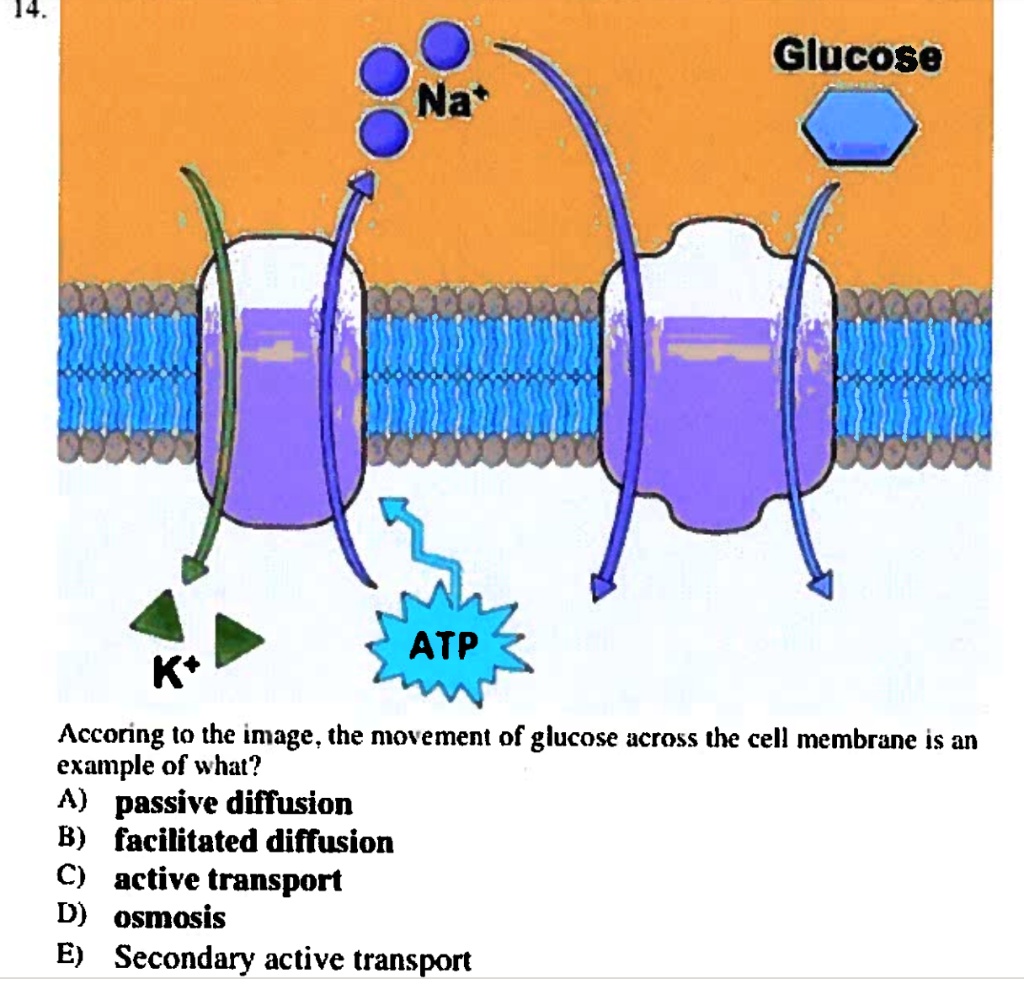

While osmosis itself demands no ATP, cellular environments where osmosis operates often do—especially when cells actively regulate solute concentrations. “Many systems maintain osmotic gradients through pumps like the sodium-potassium ATPase,” notes Dr. Rostova.These ATP-dependent transporters create solute differences that fuel secondary osmotic movements. But the actual crossing of water molecules through channels is entirely ATP-free. This distinction is critical: ATP powers the gradients that drive osmosis; it powers osmosis itself only by maintaining its prerequisites.

In highly regulated systems—such as kidney nephrons or root cells—ATP fuels ion transporters that modulate solute concentrations across membranes, indirectly sustaining osmotic movements. But water molecules move independently, guided by concentration, not energy expenditure. “You need pumps to establish gradients,” Dr.

Rostova clarifies, “but not to move water in osmosis itself.”

The Molecular Architecture Behind Osmosis

Aquaporins and the Biology of Passive Flow

A key player in efficient osmosis is the protein aquaporin, a channel embedded in cell membranes that accelerates water passage without energy cost. Aquaporins allow rapid transmembrane movement by reducing energy barriers for water molecules, yet their function depends on existing solute gradients—not on energy input. “Aquaporins are gatekeepers of hydration, optimizing flow rate where gradients exist—but they do not consume ATP,” explains Dr.Rostova. This architectural precision enables cells to respond dynamically: under low solute stress, water flows freely; under high stress, solute accumulation slows inflow. The combination of passive movement, gradient maintenance, and membrane selectivity ensures cellular hydration remains balanced with minimal energy burden.

“What we observe in physiology is a masterclass in efficiency,” Dr. Rostova asserts. “Osmosis as a phenomenon thrives on physics, not metabolism.”

Real-World Implications: Osmosis Without ATP in Nature and Medicine

From Plant Roots to Kidney Systems

In nature, osmosis powers vital functions without ATP’s direct involvement.For example, in plant cells, water uptake into root hairs and leaf cells sustains turgor pressure, enabling growth and nutrient absorption—entirely through passive osmotic gradients. Similarly, in human kidneys, osmosis facilitates fluid reabsorption in nephrons, supported by ATP-driven solute pumps but relying on passive water movement to reclaim and concentrate urine. These processes highlight osmosis’s indispensable, energy-light role in homeostasis.

It is the quiet engine that maintains cell volume, regulates blood pressure indirectly via fluid balance, and enables osmotic signaling across tissues. As Dr. Rostova observes, “Osmosis sustains life’s foundation—hydration, volume, balance—entirely by nature’s design, not an ATP toll.” Osmosis stands as a paradigm of biological efficiency: leveraging molecular structure and thermodynamics to move water without energy, allowing life to thrive where ATP is either scarce or strategically allocated.

The absence of ATP in osmosis itself reveals not a flaw, but a refinement—evolution’s answer to sustainable equilibrium. In summary, osmosis does not require ATP; it is a passive, concentration-driven process enabled by channel proteins and free energy gradients. While ATP powers the solute pumps and gradients that sustain osmotic conditions, the movement of water across membranes remains ATP-independent.

This distinction not only clarifies a core biological mechanism but celebrates the elegance of nature’s solutions—where function arises not from energy input, but from intelligent design operating within physical laws.

Related Post

Rhea Ripley’s Feet: The Hidden Power Behind Her Dominant Presence

IQ Indonesia 2025: Where National Intelligence Shapes the Future of Innovation, Work, and Society

TikToker Caca Girl’s Trauma: What We Know From Melanie And Julian Gonzalez’s Health Update

Laura Dimon: Shaping Innovation Through Strategy, Leadership, and Vision