Degenerative Diseases: Understanding Progression, Risks, and What to Expect

Degenerative Diseases: Understanding Progression, Risks, and What to Expect

From Alzheimer’s memory loss to Parkinson’s tremors, degenerative diseases represent a complex and often irreversible journey of biological decline. These conditions—characterized by the gradual deterioration of brain, nerve, or bodily tissues—affect millions worldwide, reshaping lives through unpredictable pathways. What makes them particularly challenging is not just their scientific complexity, but the profound personal and medical questions they pose: How progress?

What timelines should we prepare for? And crucially, how can individuals navigate this uncertain terrain with clarity and hope? This article dissects the core truths behind degenerative diseases, offering insight into their nature, common types, warning signs, and the realistic expectations patients and caregivers must cultivate.

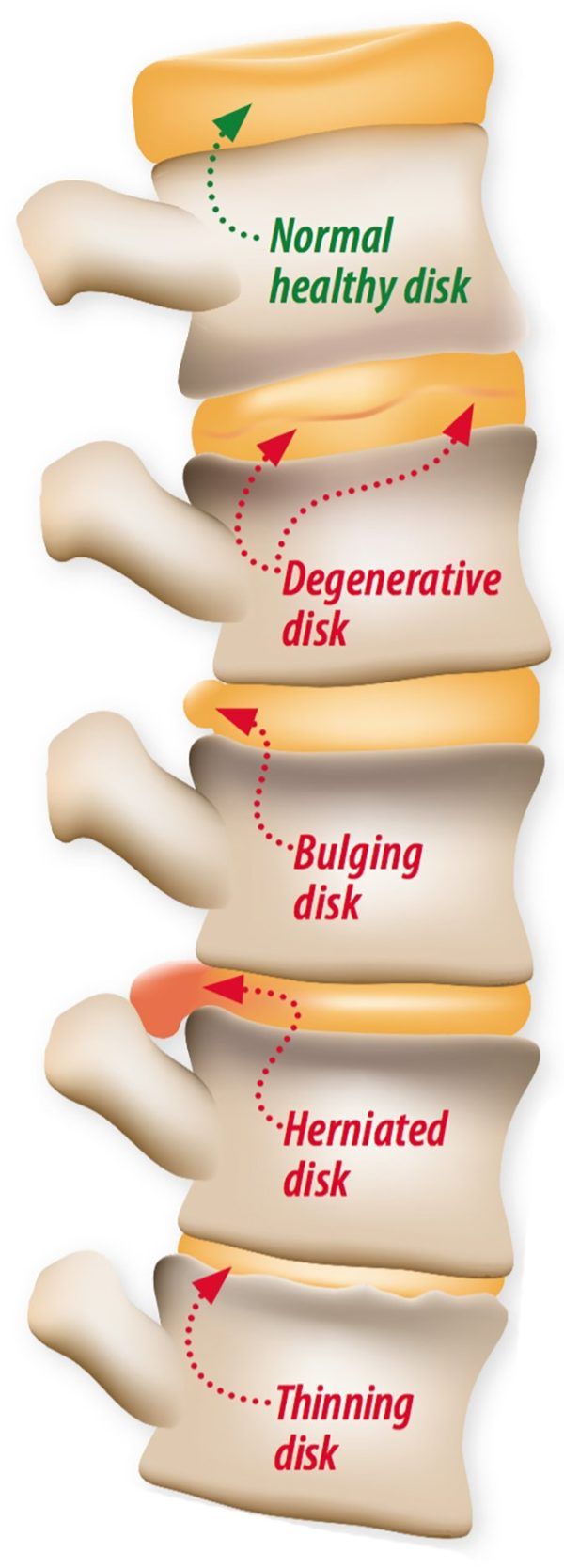

At their core, degenerative diseases are defined by progressive loss of structure or function in specialized cells or tissues. This decline undermines vital systems—neural networks, muscle control, or organ integrity—often driven by aging, genetic predisposition, or environmental triggers. While no cure exists for most, modern medicine focuses on slowing progression and maintaining quality of life.

The term “degenerate” itself comes from Latin, meaning “to decay,” but recent research reveals active cellular processes—like protein misfolding, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuroinflammation—that continually fuel disease advancement. “Degeneration is not a passiveيش العربي,” notes Dr. Elena Torres, a neurologist at Johns Hopkins.

“It’s an active biological cascade that can be monitored—and in some cases, influenced—through emerging therapies.”

Common Types and Their Unique Economic and Neurological Impact

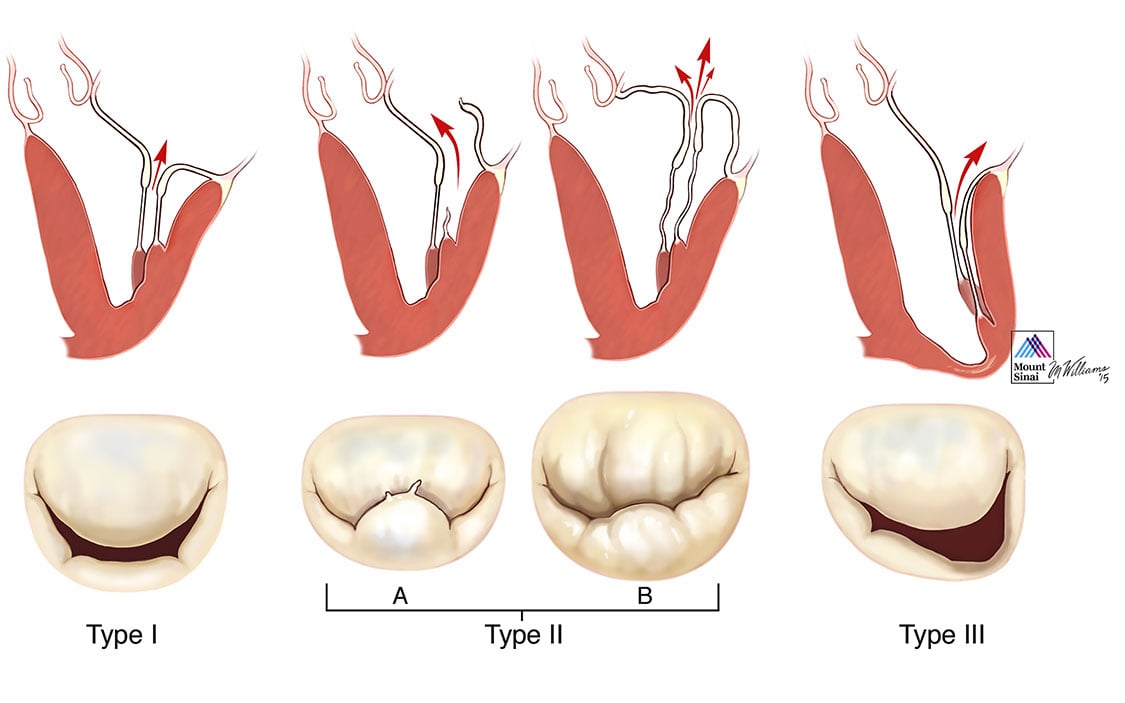

Neurodegenerative disorders dominate the landscape, with Alzheimer’s disease alone affecting over 6.5 million Americans. Alzheimer’s progressively disrupts cognition through amyloid plaque buildup and tau tangles, impairing memory, judgment, and daily functioning. Progression typically unfolds in stages—from mild forgetfulness to severe dementia—though individual timelines vary widely based on genetics, lifestyle, and comorbidities.Other major neurodegenerative conditions include: - **Parkinson’s disease**, marked by dopamine neuron loss leading to tremors, rigidity, and motor slowness. Its hallmark “bradykinesia” often follows a slow, predictable course, though non-motor symptoms like sleep disturbances and constipation worsen over time. - **Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)**, a rapidly progressive condition destroying motor neurons, resulting in muscle atrophy and loss of coordination.

Survival without treatment averages 2–5 years post-diagnosis. - **Huntington’s disease**, a genetic fault triggering neuronal death, especially in the basal ganglia, causing uncontrolled movements, emotional instability, and cognitive decline—usually in mid-adulthood. Beyond the brain, degenerative diseases extend to systemic conditions such as cardiovascular dysfunction, osteoarthritis, and type 2 diabetes—chronic states where tissue breakdown accumulates silently over decades.

Each variety demands tailored management strategies, yet shares a common thread: discreet early signs often go ignored until irreversible damage occurs.

Warning Signs and the Power of Early Detection

Recognizing early symptoms is critical, though subtle and nonspecific. While only a clinical diagnosis confirms degenerative disease, red flags frequently appear before full onset: persistent memory lapses beyond typical ‘senior moments,’ unexplained balance issues, gradual speech difficulty, or loss of fine motor control.In Parkinson’s, subtle changes like reduced facial expression or softened voice may precede visible tremors by years. “Catching these signals early can be a game-changer,” explains Dr. Rajiv Mehta, a geriatric specialist.

“Some conditions respond best to intervention at pre-symptomatic or early symptomatic stages when brain resilience is still strongest.” Routine screening—cognitive assessments, blood biomarkers, mobility testing—coupled with lifestyle monitoring (sleep, diet, physical activity)—enhances early identification. For instance, unstable gait detected in a routine check can prompt early Parkinson’s workup. The FDA has recently approved blood tests targeting specific biomarkers, offering less invasive, scalable screening tools.

“We’re moving toward a future where degeneration isn’t a surprise,” says Dr. Meah. “A simple symptom combined with biomarker data may one day trigger timely intervention.”

Navigating the Uncertain Timeline: What Progression Really Looks Like

One of the greatest challenges in degenerative disease is reconciling scientific data with real-world experience.Progression rarely follows a clear curve; fluctuation, remission, and variable pace are common. For Alzheimer’s, clinical trials indicate averages of 5–7 years from diagnosis to advanced stages, yet some patients manage decades of meaningful function, particularly if diagnosed early. The same holds for Parkinson’s, where individual trajectories range from slow decline to accelerated progression within a few years.

Medications, therapies, and supportive treatments can significantly alter this arc. While not curative, drugs like cholinesterase inhibitors stabilize Alzheimer’s cognition in some, and dopamine agonists extend mobility in Parkinson’s. Multidisciplinary care—including physical therapy, speech treatment, and psychological support—mitigates symptom burden and improves function.

Equally vital is caregiver adaptation: structural planning, respite care, and emotional preparedness reduce burnout and enhance quality of life. “Every patient’s journey is unique,” emphasizes Dr. Torres.

“Advance care planning—discussing goals, preferences, and realistic expectations—empowers individuals to take control, even amid uncertainty.” In practice, patients and families increasingly rely on patient registries and digital health platforms to track symptoms, treatment responses, and research advances in real time.

Lifestyle, Prevention, and the Road Ahead

While genetics anchor many degenerative risks, growing evidence highlights modifiable factors. A heart-healthy diet rich in antioxidants, sustained aerobic exercise, cognitive stimulation, and strong social connections correlate with delayed onset or reduced severity.Sleep disorders, chronic stress, and exposure to environmental toxins compound risk—making holistic wellness a preventative stronghold. Emerging therapies—including gene editing, stem cell research, immunotherapies targeting protein aggregates, and neuroprotective agents—offer cautious hope. Yet these advances remain experimental for most conditions, underscoring the current reliance on established supportive care.

“Prevention isn’t just for longevity,” notes Dr. Mehta. “It’s about preserving function, independence, and dignity.”

Degenerative diseases challenge both science and society with their quiet persistence and variable impact.

While their progression cannot be halted today, understanding, early detection, and proactive management empower patients and caregivers to face each stage with resilience. The message is clear: knowledge is not powerlessness. With continued research, compassionate care, and informed patience, individuals navigate this segmented trajectory not just as survivors—but as stewards of their own well-being.

Related Post

Decode the Spelling Bee Success: Reddit’s Top Hints That Top Pollinators Swear By

Kimrie Lewis: Star Power, Personal Life, and the Truth Behind the Hometown Actress

Celebrity Movie Archive Reveals Alist Stars’ Most Shocking On-Screen Transformations: When Stars Shocked the World