Define Irrational Number: The Enduring Mystery Behind Non-Repeating, Non-Terminating Decimals

Define Irrational Number: The Enduring Mystery Behind Non-Repeating, Non-Terminating Decimals

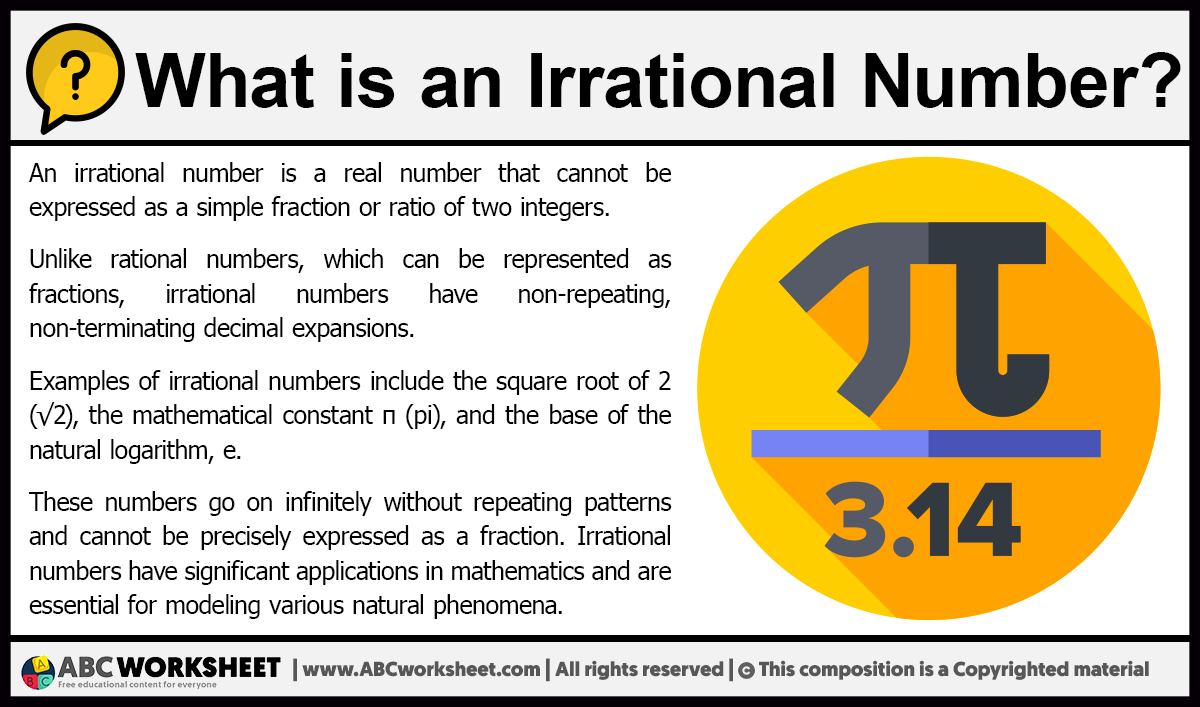

Irrational numbers define one of mathematics’ most fascinating and counterintuitive frontiers—real numbers that cannot be expressed as a ratio of two integers, resulting in infinite, non-repeating decimal expansions. Unlike fractions or whole numbers, these enigmatic values defy simple expression, embodying both precision and unpredictability. Their existence challenges human intuition, weaving deep into number theory, geometry, and computational science.

From the curvature of the circle to the dynamics of chaos, irrational numbers shape the very grammar of mathematical reality.

What Makes a Number Irrational? The Core Definition

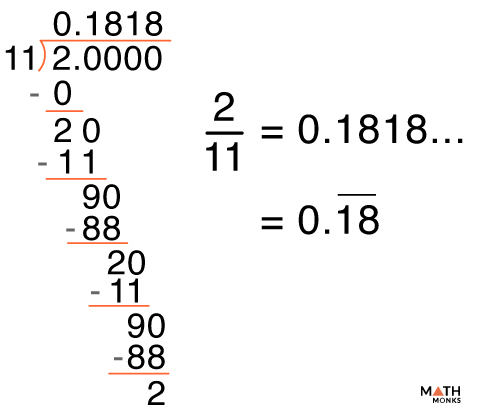

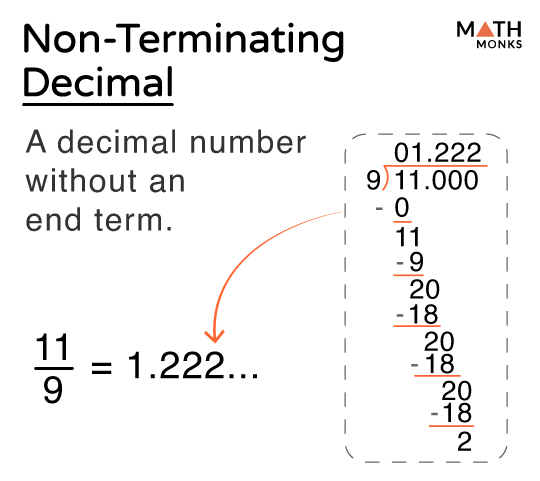

At its mathematical core, an irrational number is any real number that cannot be written in the form a/b, where a and b are integers and b is non-zero. This definition excludes rational numbers—such as ½ (which equals 0.5) or ⅔ (0.666...)—whose decimal forms terminate or repeat endlessly.

Irrational numbers, by contrast, produce decimal expansions that neither end nor settle into a cycle. The very term “irrational” derives from the Latin *irrationalis* (“not rational”), coined by 18th-century mathematicians critical of the inability to express certain lengths—like the diagonal of a unit square—with whole-number ratios.

This distinction is fundamental. Consider the square root of 2.

Since no fraction a/b yields (a/b)² = 2 exactly, √2 cannot be written as a ratio and thus occupies the irrational domain. “Irrationality is not just a property—it’s a boundary between the describable and the infinitely elusive,” observes mathematician Dr. Elena Marquez.

“It reveals the limits of finite language within the infinite continuum of real numbers.”

Classic Examples: The Pioneers of Irrationality

Some of the most renowned irrational numbers anchor mathematical history. The simplest is π (pi), the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter, approximately 3.14159… recurring infinitely without repetition. Equally iconic is √2, first proven irrational by the ancient Pythagoreans, who were stunned to discover that the diagonal of a square with unit sides couldn’t be captured as a fraction.

Other constants further illustrate the scope of irrational numbers: φ (phi), the golden ratio (~1.618...), emerges from elegant geometries and proportions; e, the base of natural logarithms (~2.718...), governs exponential growth and decay; and √π, a hybrid irrational linking geometry and analysis.

These numbers are not theoretical oddities—they appear ubiquitously in physics, engineering, and nature.

Decimal Behavior: Infinite, Non-Repeating, and Unpredictable

One of the most striking traits of irrational numbers is their decimal expansion: infinite and non-repeating, with no discernible pattern. Take 1/√2 ≈ 0.70710678118…—the digits continue forever, never falling into a loop. In contrast, rational decimals either terminate (0.75) or cycle (0.333...)—patterns detectable by simple observation.

This inherent chaos makes irrational numbers inherently difficult to pin down, even though their rules are mathematically precise.

To quantify unpredictability, researchers use statistical measures. The digits of π, for example, pass rigorous tests for normality—meaning every digit sequence appears with equal statistical probability. While not fully proven, this suggests a form of digital randomness.

For many irrationals, such as the golden ratio or ‘e’, digit distributions remain well-understood, yet not predictable or periodic. “Irrational numbers embody controlled randomness,” explains number theorist Dr. Rajiv Patel.

“Their surface appears chaotic, but lies beneath layers of mathematical design.”

Geometric Roots: The Birth of Irrationality in Classical Mathematics

The concept of irrational numbers emerged from geometry, not arithmetic. The ancient Greeks, particularly the Pythagoreans, believed all magnitudes could be measured using whole-number ratios. The proof that √2 is irrational shattered this worldview.

According to legend, Hippasus of Metapontum may have been the first to demonstrate √2’s irrationality through geometric reasoning—showing that no finite fraction could equal the diagonal of a unit square.

This discovery altered mathematics, leading to a deeper appreciation of limits, infinity, and the real number line. Euclid’s Elements later formalized irrational magnitudes via geometric construction, separating number from measurable length. Today, such numbers underpin calculus, trigonometry, and topology—disciplines essential to modern science and technology.

Infinite Precision: The Challenge of Representing Irrational Numbers

Despite their fundamental role, irrational numbers resist exact, finite representation.

In computer science, a value like π is stored as an approximation—e.g., 3.141592653589793—truncated to a few decimal places. This limitation reveals a paradox: while irrationals define precise mathematical truths, their infinite nature demands pragmatic approximations in computation.

This tension drives innovation in numerical methods. Scientists and engineers use algorithms to extract irrational constants to hundreds or thousands of digits for high-precision computing, cryptography, and space exploration.

“We manage irrationals not by grasping them fully,” notes computational mathematician Dr. Lin Wei, “but by leveraging their predictable statistical behavior within bounded error margins.”

Interestingly, not all infinite decimals are irrational. A sequence with a repeating block, such as 0.101010… = 1/9, remains rational.

Irrationality arises when no such cycle exists—infinite aperiodicity embedded in infinity itself.

Irrational Numbers Beyond Mathematics: Nature, Physics, and Art

Irrational numbers permeate the natural world long before human notation. The golden ratio φ manifests in spirals of sunflower seeds, nautilus shells, and galaxy arms—patterns optimized for efficiency and resilience. Fibonacci sequences, closely tied to φ, govern growth in biology and growth symmetry.

In physics, constants like π define wave behavior and orbital mechanics.

The quantum realm, too, relies on irrationals: energy levels, uncertainty principles, and quantum field theories frequently involve transcendental numbers like e and π. Even chaos theory—exploring unpredictable systems—depends on irrational parameters to model real-world complexity, from weather patterns to stock markets.

The arts, too, echo irrational harmony

Related Post

Jameliz Benitez Smith: Career Trajectory, Influence, and Legacy Across Platforms