Decoding Development: How Course Units Illuminate the Path to Global Progress

Decoding Development: How Course Units Illuminate the Path to Global Progress

Development Studies offers a vital framework for understanding the complex, interconnected forces shaping societies across the Global South and beyond. At its core lies a structured curriculum built around key course units, each unpacking critical theories, methodologies, and real-world applications. These units transform abstract development concepts into actionable knowledge, equipping students and practitioners with tools to analyze, evaluate, and influence development outcomes.

From postcolonial critiques to sustainable innovation, the study of development unfolds not as a static discipline but as a dynamic, evolving dialogue—one driven by the deliberate examination of specialized course modules. This article breaks down the principal course units in Development Studies, revealing how they collectively illuminate the challenges and opportunities of building equitable, resilient futures.

Central to the discipline is a modular curriculum designed to build both theoretical depth and practical insight.

Each unit advances specific learning outcomes, integrating interdisciplinary perspectives from economics, political science, sociology, and environmental studies. The sequencing of units follows a progressive logic: beginning with foundational critiques of development paradigms, then advancing to tools for analysis, intervention, and advocacy. This deliberate structure ensures learners grasp not only *what* development means, but *how* it is studied, measured, and transformed in diverse contexts.

Unit 1: Foundations of Development Thinking – Decolonizing Knowledge and Postcolonial Critique

At the outset, students confront the historical and ideological roots of development theory. Course Unit 1 dismantles the Eurocentric assumptions long embedded in mainstream development discourse. By examining postcolonial thinkers such as Frantz Fanon and Walter Rodney, learners analyze how colonial extraction and structural dependency continue to shape global inequalities today.“Development is not a neutral process,” argues scholar Arjun Appadurai, “it is deeply entangled with histories of domination.” This unit establishes a critical lens, urging students to question who defines progress and whose voices are centered—or silenced—in development narratives. Students engage with core concepts like dependency theory, modernization theory, and the politics of knowledge production, laying a foundation for more reflexive engagement with global development.

Equally important is the unit’s focus on ethical responsibility.

Students debate whether development, as traditionally practiced, reproduces neocolonial power dynamics or offers genuine pathways to empowerment. Case studies from Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia illustrate both failures and successes, reinforcing that context-specific understanding is non-negotiable. By integrating these critiques, Unit 1 emphasizes that effective development work begins with a clear-eyed diagnosis of power imbalances.

Unit 2: Methodologies in Development Research – Tools for Analysis and Evidence-Based Practice

Armed with critical awareness, students progress to the methodological foundations of development study. Unit 2 focuses on the research tools and analytical frameworks that enable rigorous investigation into development challenges. This unit emphasizes both qualitative and quantitative approaches, from mixed-methods surveys to participatory rural appraisal techniques.Students learn how to deploy indicators—such as the Human Development Index or multidimensional poverty measures—to assess achievement and inequity.

Key methods explored include longitudinal studies, impact evaluations, and gender-disaggregated data analysis, each crucial for evaluating interventions accurately. The course stresses the importance of triangulation—using multiple data sources and perspectives—to mitigate bias and enhance validity.

Real-world exercises, such as analyzing World Bank datasets or designing a theoretical framework for a community health project, ground theory in practice. As development scholar David Hulme notes, “Good research is not just about collecting data—it’s about asking the right questions.” This unit empowers learners to become skilled analysts capable of contributing meaningful insights to policy and practice.

Unit 3: Poverty, Inequality, and Social Justice – Threads of Distress and Resistance

No exploration of development is complete without confronting poverty and inequality in all their multidimensional forms.Unit 3 delves into the structural drivers of deprivation and strategies for social justice. Students examine macro-level forces—global financial systems, trade policies, tax regimes—alongside micro-level realities of marginalized communities. The unit moves beyond statistics to reveal human stories, emphasizing that poverty is not merely economic but deeply rooted in exclusion based on class, gender, ethnicity, and geography.

The course introduces frameworks such as Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach, which broadens evaluation from income to freedoms and opportunities. Students analyze case studies—from microfinance initiatives in Bangladesh to land reform movements in Brazil—to assess how policies either entrench or reduce inequity. Debates center on redistributive justice, universal basic

Related Post

Mahesh Babu Sister: Redefining Family, Legacy, and Leadership in South Indian Cinema

SCP-169: The Dismantled Prison That Devours Time—and Memory

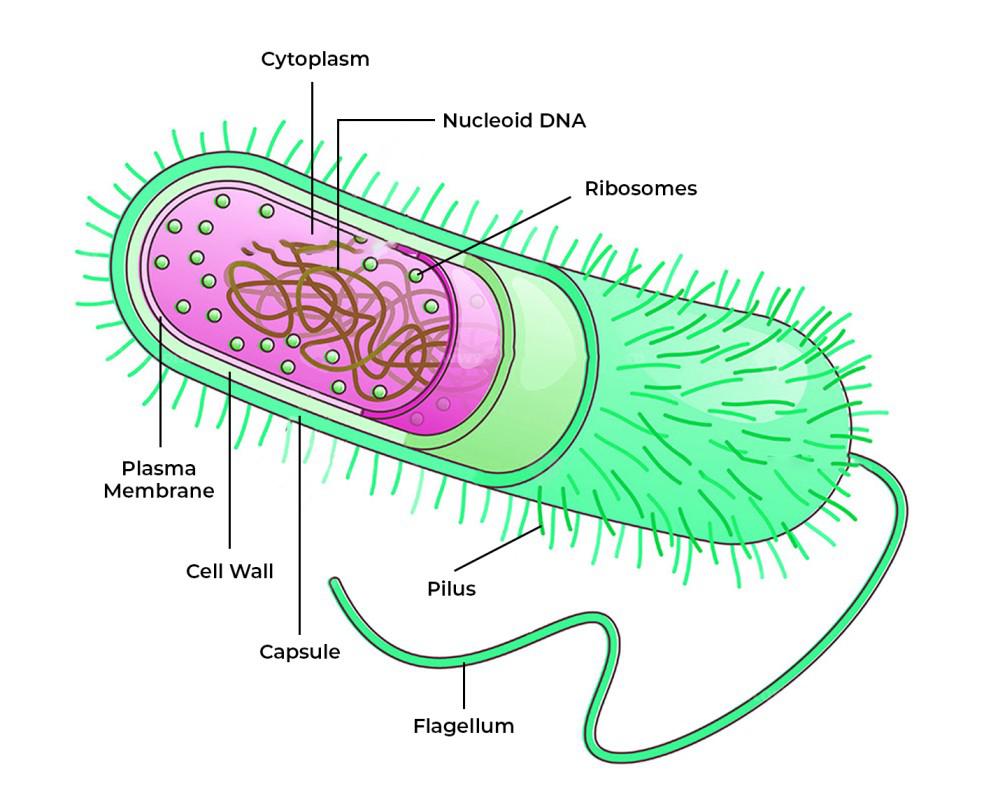

Do Prokaryotic Cells Have Vacuoles?