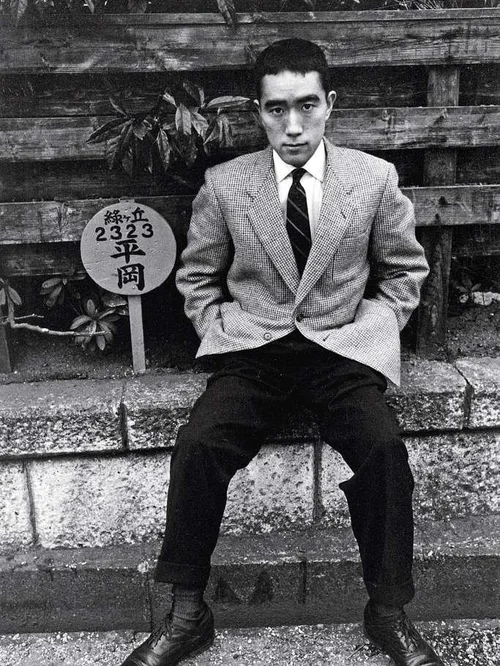

Circus Yukio Mishima: The Daring Spectacle of a Literary and Theatrical Grandmaster

Circus Yukio Mishima: The Daring Spectacle of a Literary and Theatrical Grandmaster

Yukio Mishima, the towering figure of postwar Japanese literature, extended his influence beyond prose into a performative, almost circus-like mastery of stage, body, and ideology—one where discipline, spectacle, and existential rebellion converged in an electric theatrical form. Far more than a novelist, Mishima choreographed men, myths, and movements with precision, creating a personal “circus” of self; a living arena where power, aesthetics, and tragedy merged on a grand scale. His theatrical persona, amplified through performances, public rituals, and ultranationalist spectacle, embodied a unique fusion of artistry and manifesto—unwelcome by many, but enduringly fascinating.

Mishima’s early immersion in traditional Japanese theater profoundly shaped his sensibility. Educated in Noh and Kabuki, forms steeped in ritualized movement and symbolic intensity, he absorbed a reverence for *ma*—the space between motion—blending discipline with dramatic impact. This foundation informed not only his writing but also his stage presence: every gesture, pause, and costume was symbolically layered, akin to a moving play deeply rooted in cultural memory.

His performances, whether in adaptations of classical works or personal interpretations, relied heavily on physical discipline, transforming the human body into a canvas of emotion and meaning. What elevated Mishima’s artistic identity into circus territory was his belief that life itself could be performance. He orchestrated public acts with theatrical flair, turning political statements into staged ceremonies.

The most infamous example is his 1970 ritual suicide, *Seppuku*, carried out at the Tōshō-gū Shrine with samurai precision—ritualized no less than a tragic finale to a lifelong theme. This spectacle was not shock for shock’s sake; it was meticulously choreographed, intended as a living declaration against modernity’s moral decay. In his view, death in such form was not an end, but a grand, irreversible climax—an eternal tableau of defiance.

The Art of Disaster: Theater as Political Ritual

Mishima’s theatricality was inseparable from his radical ideology. His performances were acts of resistance—ceremonial explosions meant to shock Japan into reclaiming its spiritual and martial essence. He saw the nation’s postwar pacifism and Westernization as spiritual bankruptcy, a crisis that required a return to discipline, honor, and sacrifice.Hishaftungen—performative awakenings—were not mere pageantry but aggressive statements against what he called “moral laxity.” Programs from his public appearances reveal a deliberate aesthetic: traditional attire woven into modern choreography, calligraphy unfurling like stage script, and choreography designed to awe as much as to provoke. Each event was structured like a theatrical act: pacing, silence, and symbolic escalation culminating in irreversible gesture. This fusion of ritual and rebellion transformed political dissent into living mythology.

A pivotal moment came in 1968 with the founding of the Shield Violence (Bakuten no Kai), a private militia meant to “restore honor” through disciplined confrontation. Though short-lived, the movement embodied Mishima’s theatrical ideology—performance not confined to stage but enacted through physical readiness and symbolic action. His suicide, staged as a *kata*—a premeditated, scandalous finale—was the ultimate proof of belief: life enacted as art, with death the final, unavoidable act.

The Stage of the Self: Mishima as His Own Performer

Mishima’s autobiographical works deepen the understanding of his circus-like existence. *Confessions of a Mask*, a psychological tour de force beneath the public persona, reveals a man torn between societal expectations and an inner self yearning for transcendence. Publicly, he embodied the disciplined intellectual; privately, he performed a hidden, agonized journey toward a synchronized soul-body unity.His theatrical training, particularly in Noh, is evident in his writing: sparse yet charged with symbolic resonance, his prose often strips away excess to focus on gesture and presence. In *The Temple of the Golden Pavilion*, the protagonist’s compulsive beauty obsession mirrors Mishima’s own obsession with aesthetic perfection and self-control—an artistic discipline extended into his personal discipline. He walked, wrote, and fought with the precision of a performer under perpetual stage lighting.

Performance extended to daily life: public recitations of poetry, public reenactments of historical acts, even carefully staged confrontations. His final act—writing *The Decision to Die* (also titled *The Ceremony*) in raw, blood-streaked ink—was not madness but culminating theater: a final, irreversible performance authored on the stage of history.

He challenged postwar complacency through spectacle, forcing society to confront uncomfortable truths about identity, tradition, and nationhood. His fusion of literature, physical mastery, and ritualized politics remains a complex, provocative model of artistic self-creation. Far from a mere literary icon, Mishima was a performer of culture—one who turned life into theater, ideologies into spectacle, and death into a final, unforgettable act.

In this, he embodied a true circus: unpredictable, electric, and unforgettably human. His legacy endures not just in the pages of his novels, but in the vivid, harrowing performance he staged until his final breath.

Related Post

Dodgers Promotions 2025: Game-Changing Fan Experiences Set to Redefine Baseball’s Future

Dawn Ostroff Spotify Supernatural Email Bio Wiki Age Height and Net Worth

Yankees vs Dodgers: A Generational Rivalry Forged in Numbers, Glory, and Fire

<strong>Tusd Board’s DEI Guidelines Vote Sparks Bookstore-Centric Policy Shift Amid Growing Educational Equity Demand</strong>