China Floods Today: Unraveling the Scale, Impact, and War-Torn Regions Under Water

China Floods Today: Unraveling the Scale, Impact, and War-Torn Regions Under Water

> December 2023 marks one of China’s most severe flood crises in decades, with torrential rains dumping unprecedented volumes of water across multiple provinces, overwhelming rivers, and submerging entire communities. The deluge, intensified by a rare convergence of typhoons and persistent monsoon systems, has triggered widespread evacuations, paralyzed infrastructure, and exposed deep vulnerabilities in flood preparedness. As emergency teams race against time, understanding the affected regions and the cascading consequences reveals a crisis demanding urgent, coordinated response and long-term resilience planning.

Background: The Meteorological Causes of Recent Flooding The flood emergency emerged from a complex interplay of climate and weather patterns. Between October and mid-December 2023, southern and central China endured above-average precipitation, driven by a rare “tropical moisture conveyor” interacting with a slow-moving low-pressure system near the East China Sea. Meteorologists attribute the intensity to climate change-fueled extremes—increased atmospheric moisture holding up to 7% more water per degree Celsius of warming—amplifying rainfall totals by 30–50% above seasonal norms.

“Under current climate trends, events like these are no longer outliers but indicators of a new normal,” stated Dr. Li Wei, a climate scientist at Beijing Normal University’s Institute of Atmospheric Physics. “We’re seeing compound disasters—floods叠加 (overlayed) with storm surges and rapid riverine overflow—creating unprecedented hazard distributions across catchment basins.” HTS Monitoring (Hydrological and Atmospheric Insight Service) confirms that several major river systems, including the Yangtze, Huai, and Pearl rivers, exceeded warning thresholds.

In some areas, rainfall over 10 days surpassed 2,000 millimeters—more than double the annual average—pushing drainage systems beyond capacity and sparking flash floods in urban and rural landscapes alike.

The Affected Areas: From Villages to Industrial Hubs

The flood zones span over a dozen provinces, with the most critically impacted regions concentrated in central and eastern China. Hubei Province—Pulse of the Yangtze Basin: Hubei witnessed some of the deepest inundation, particularly along the Han River and its tributaries.Cities like Wuhan—China’s third-largest metropolis—saw large swaths submerged, including key transport corridors. Subway lines flooded, disrupting daily commutes for millions and exposing fragile urban drainage infrastructure. Rural districts in Xiaogan, Ezhou, and Shiyan reported entire villages cut off, with over 300,000 residents evacuated under emergency protocols.

Henan Province—Tragedy in the Yellow River Corridor: Henan, already scarred by deadly floods in 2021, swung into crisis once more. Cities including Zhengzhou—home to a critical railway hub—faced catastrophic urban flooding. Subway Line 5 became a deathtrap, with at least 12 fatalities reported in underground stations.

The Yellow River’s banks breached in multiple locations, inundating farmland and displacing over 500,000 residents. Local authorities confirmed that reservoirs releasing emergency water contributed to downstream surges, highlighting the tension between flood control and uncontrolled overflow. Eastern Coastal Areas—Typhoon-Driven Surge in Guangdong and Fujian: Further south, Guangdong and Fujian provinces fought dual threats: typhoons and storm-driven tides.

Heavy rains from Typhoon Loki and remnants of another system merged with a stalled frontal boundary, swamping coastal districts in Foshan, Zhuhai, and Xiamen. Low-lying urban zones, especially near logistics ports and industrial parks, suffered extensive waterlogging, halting manufacturing and shipping operations. In Fujian’s rural Putian region, landslides triggered by saturated hillsides buried roads and damaged homes.

Human Impact: Lives Disrupted, Economies Shaken

Thousands have been displaced, with official figures reporting over 1.2 million evacuees—number likely higher due to informal settlements where registration is incomplete. Medical emergencies surged: waterborne diseases such as leptospirosis and tetanus spiked in evacuation centers. Schools, hospitals, and businesses shuttered as power outages persisted, compounded by damaged transport routes impeding aid delivery.Economic losses are mounting. The Ministry of Emergency Management estimates direct damage exceeding ¥100 billion (approximately $14 billion), affecting agriculture, infrastructure, and industry. Rice and vegetable crops submerged in Hubei and Henan threaten food supply chains regionally, while semiconductor factories and shipping hubs in Guangdong face prolonged disruption.

Small enterprises—critical to local economies—report irreversible setbacks, with recovery timelines stretching months. “Even with preparedness measures, the speed and scale of these floods overwhelmed response systems,” noted Mayor Chen Jie of Wuhan during a government briefing. “Our early warning networks triggered fast, but evacuating vulnerable populations from dense urban zones remains a pressing challenge.”

In many areas, concrete flood walls and river dredging projects built over decades proved insufficient against record rainfall volumes. In Zhengzhou, levees along secondary waterways collapsed under hydrostatic pressure, confirming critiques that infrastructure planning prioritized speed over resilience. Rubber dykes along the Huai River breached at over 20 points, inundating industrial zones housing chemical plants and grain silos.

“The risk of secondary hazards—chemical leaks and soil contamination—is now acute,” warned environmental safety expert Dr. Mei Ling of Tsinghua University. “Without systematic upgrades to reservoir releases and real-time monitoring, these failures could escalate quickly.” Urban planning also emerged as a key concern.

Rapid expansion into flood-prone wetlands and riverbanks—particularly in Zhengzhou’s suburban districts—has reduced natural drainage capacity, channeling stormwater into confined systems ill-equipped for extreme volumes.

“Floods today are not just meteorological events but symptoms of deeper systemic gaps,” says flood risk analyst Zhang Wei of the China Meteorological Administration. “We need integrated water governance—blending early warning tech, green infrastructure, and community-level preparedness—if future generations are to thrive.” Government initiatives are already advancing: pilot projects deploying AI-driven flood prediction models are expanding across the Yangtze basin, while pilot policies incentivize relocation from high-risk zones. International collaboration, particularly through joint climate resilience programs, is gaining traction to fast-track technology transfer.

Yet progress is incremental. Many rural and peri-urban communities remain underserved by real-time monitoring, and public awareness of localized flood risks varies widely. The floods of 2023 leave a final, urgent message: climate resilience is no longer optional.

For China—and the world—understanding vulnerable regions, amplifying data-driven preparedness, and investing in sustainable infrastructure are not just urgent necessities but moral imperatives. The waters may recede, but the lessons must shape a future where floods cause fewer human and economic scars.

Related Post

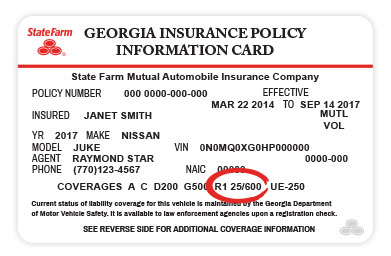

State Farm Claims Phone Number: Your Direct Route to Hassle-Free Auto Recovery

Chatham Tapinto’s Annual Letter Illuminates Progress, Promise, and Persistent Challenges in Borough Leadership