Cell Respiration vs Fermentation: The Battle for Energy in Living Cells

Cell Respiration vs Fermentation: The Battle for Energy in Living Cells

In the microscopic theater of life, energy conversion defines survival. At the heart of cellular metabolism lie two pivotal processes—cell respiration and fermentation—each representing distinct strategies cells deploy to convert nutrients into usable energy. While both pathways transform glucose into ATP, their mechanisms, efficiency, and biological contexts diverge profoundly.

Understanding the differences between cell respiration and fermentation reveals not only the elegance of cellular biochemistry but also the evolutionary adaptations that enable organisms to thrive in vastly different environments.

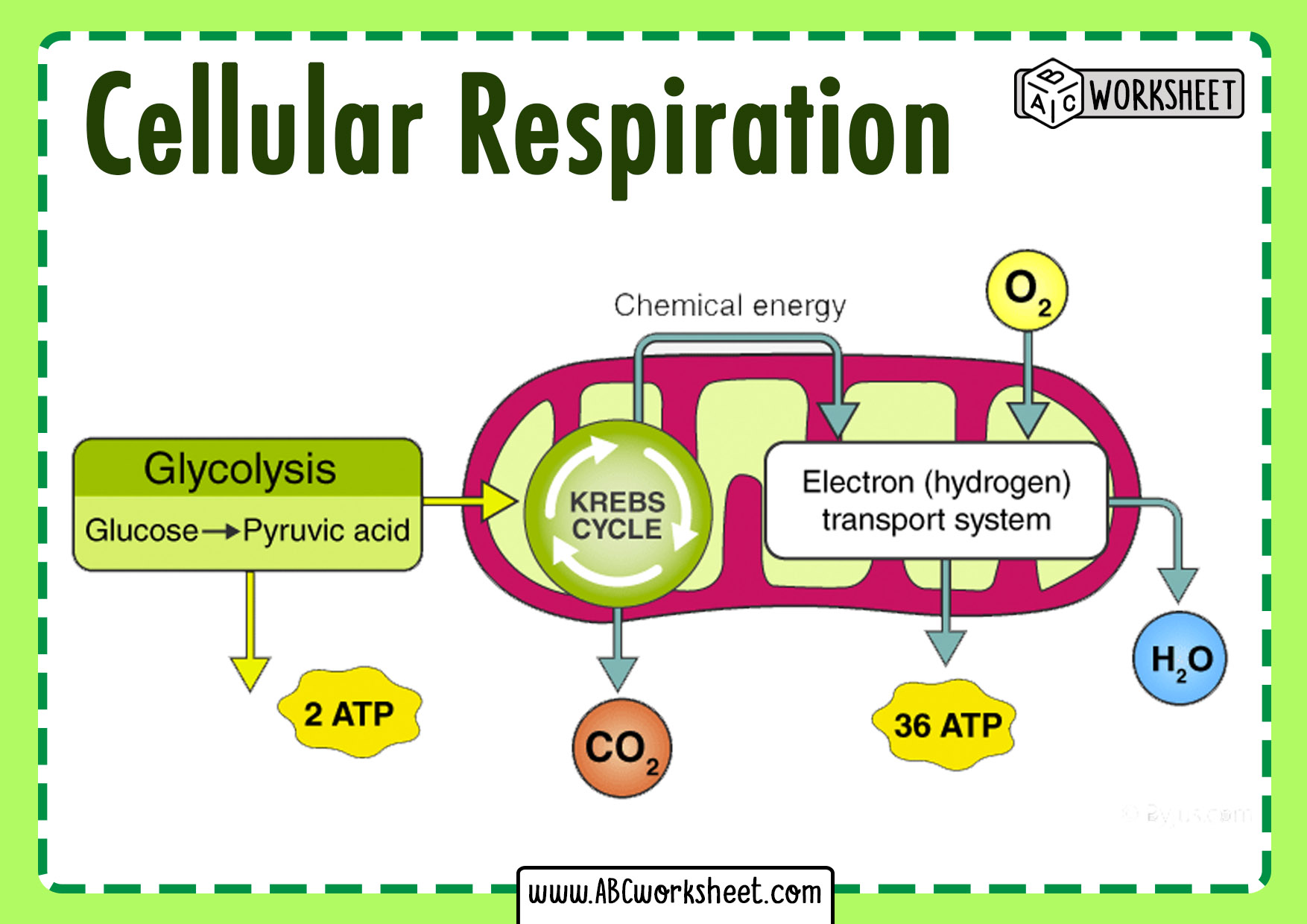

Cell respiration is the oxygen-dependent pathway through which cells extract energy from glucose with remarkable precision, yielding up to 36 ATP molecules per glucose molecule. In contrast, fermentation is an anaerobic alternative, producing only two ATPs per glucose but operating efficiently in oxygen-deprived conditions.

These divergent routes underscore a fundamental biological trade-off: efficiency versus resilience. "While aerobic respiration is the gold standard for energy yield, fermentation provides a critical survival mechanism when oxygen availability is limited," explains Dr. Elena Marquez, a biochemist specializing in energy metabolism at the University of Cambridge.

The Core Difference: Energy Yield and Oxygen Dependence

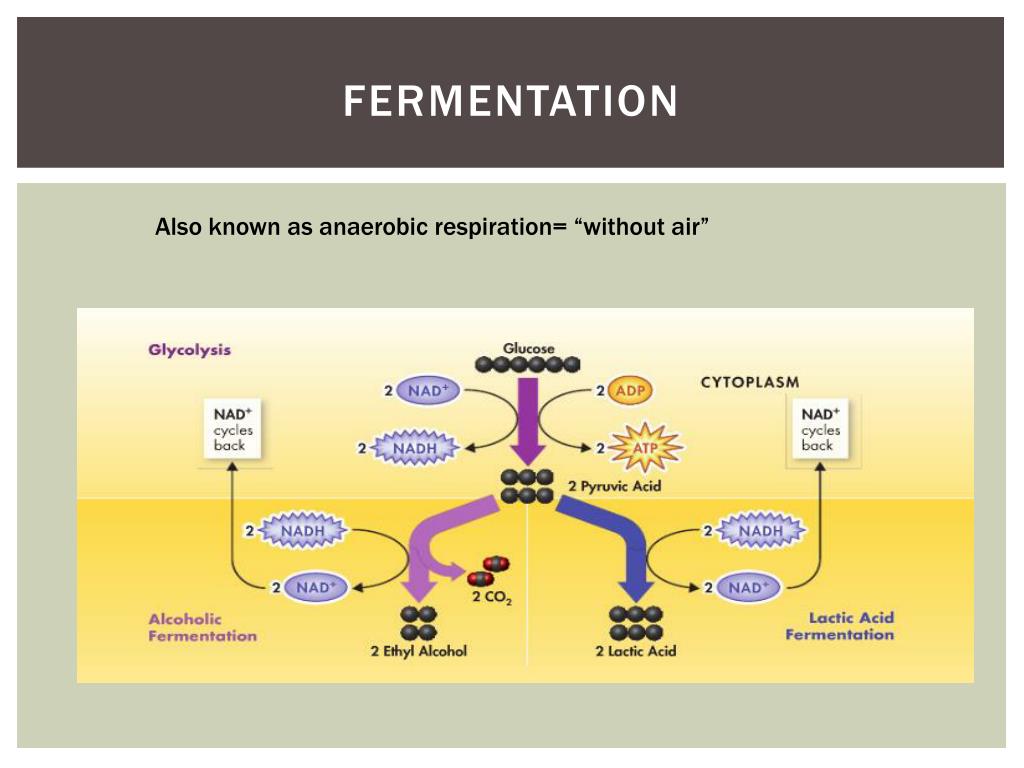

At the biochemical level, cell respiration and fermentation represent two solutions to the same challenge: generating adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the cell’s primary energy currency. Cell respiration relies entirely on oxygen as the final electron acceptor in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. This reliance enables electrons to flow efficiently through a series of redox reactions, driving proton leakage across the inner mitochondrial membrane and ultimately producing a robust ATP output.By contrast, fermentation occurs entirely in the cytoplasm and bypasses the electron transport chain. Instead of oxygen, organic molecules—such as pyruvate—serve as electron acceptors. During fermentation, pyruvate undergoes a series of chemical transformations, regenerating NAD+ to sustain glycolysis, the initial stage of glucose breakdown.

This regeneration allows glycolysis to continue producing two ATPs per glucose, though far less than respiration.

The oxygen dependence of respiration creates a critical limitation: it only functions in environments where oxygen is accessible. Fermentation, devoid of this requirement, empowers cells to generate energy in extreme conditions—such as deep tissues, anaerobic soil layers, or the intestinal tracts of animals and humans during intense exertion.

Protocols in Action: Glycolysis and Beyond

Despite their divergence, both processes begin with glycolysis—the universal first stage where one glucose molecule is split into two pyruvate molecules, yielding a modest net gain of two ATPs and two NADH.From here, the pathways split dramatically based on oxygen availability. In aerobic conditions, pyruvate enters the mitochondria, where it is converted to acetyl-CoA and fuels the Krebs cycle. High-energy electrons from acetyl-CoA flow through the electron transport chain, driving ATP synthesis through oxidative phosphorylation—a process capable of generating up to 34 additional ATPs, for a total of 36–38 ATP per glucose.

When oxygen is absent or severely limited, cells switch tactics. Pyruvate, rather than proceeding to mitochondria, is converted via fermentation enzymes into end products such as lactic acid or ethanol and carbon dioxide. This transformation does not produce ATP beyond glycolysis but ensures NAD+ regeneration, keeping glycolysis operational for as long as needed.

Types of Fermentation: Who Uses Which Pathway?

Fermentation is not a single process but a family of alternatives shaped by evolutionary adaptation. Lactic acid fermentation, employed by human muscle cells during intense exercise and many bacteria like *Lactobacillus*, regenerates NAD+ swiftly, sustaining brief bursts of activity. This process provides energy quickly but without long-term efficiency.Alcoholic fermentation, practiced by yeast and certain fungi such as *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, splits pyruvate into ethanol and CO₂. This pathway, crucial for bread leavening and biofuel production, highlights fermentation’s role in industrial and ecological cycles. Lactic acid fermentation also dominates rice and certain tissue metabolism in mammals.

During strenuous activity, oxygen supply lags behind demand, forcing muscle cells into lactic fermentation and resulting in lactic acid accumulation—a key cause of fatigue and delayed recovery.

Efficiency and Practical Implications

The disparity in ATP yield between respiration and fermentation reveals a clear hierarchy: respiration delivers precision and power, while fermentation delivers speed and survival. Aerobic respiration extracts up to 34 times more energy per glucose molecule, but only if oxygen is available.In hypoxic or anaerobic environments, fermentation becomes indispensable, offering a lifeline when oxygen is scarce. Biologically, this trade-off reflects evolutionary optimization. Organisms in oxygen-rich environments maximize energy through respiration.

In contrast, organisms adapted to anaerobic niches—including gut microbiomes, deep-soil microbes, and resting human cells—leverage fermentation to persist where respiration would fail. Fermentation also feeds human innovation. From brewing industries to biofuels, understanding fermentation enables control over microbial metabolism for economic and technological benefit. Industrial fermentation, for instance, powers the production of antibiotics, enzymes, and renewable fuels by cultivating engineered yeast and bacteria in oxygen-limited bioreactors.

Conversely, cell respiration’s dominance in aerobic organisms underscores its role in sustaining complex life forms that demand high, sustained energy output. The human brain, Rica seeing its voracious oxygen consumption, depends largely on aerobic respiration, highlighting how intricately biology couples energy systems with physiological function.

Environmental and Health Frontiers

Beyond immediate energy production, the interplay between respiration and fermentation shapes ecological dynamics and human health.In nitrogen-poor soils, fermenting bacteria sustain nutrient cycling even under low-oxygen conditions, supporting plant growth and ecosystem stability. In the human gut, commensal microbes switch between respiration and fermentation based on local oxygen and substrate availability, influencing digestion, immune function, and disease risk. In medicine, understanding fermentation is critical to treating metabolic disorders.

For example, lactic acidosis—a buildup of lactic acid during intense exercise or sepsis—stems from excessive fermentation. Conversely, cancer cells often increase fermentation (the Warburg effect) despite abundant oxygen, bypassing respiration to fuel rapid proliferation. This metabolic rewiring presents both diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets.

In environments ranging from deep ocean vents to human tissues, the rivalry between respiration and fermentation continues to shape life at both microscopic and global scales. The balance between energy efficiency and functional resilience reflects nature’s intricate engineering—where form follows function, and survival dictates pathway choice.

A dance of adaptation

Cell respiration and fermentation together form a dynamic metabolic duet. While respiration dominates in energy-rich settings,

Related Post

The 2025 Military Pay Chart: A Breakdown of Fresh Salaries That Shape Defense Careers

Niki Arcade Craniacs Age Wiki Net worth Bio Height Boyfriend

Jamie Genevieve Biography Age Wiki Net worth Bio Height Boyfriend

Taylor Hill’s Ethnicity: Navigating Identity in a Multicultural Spotlight