Catalysts: The Invisible Architects Transforming Reactants into Products

Catalysts: The Invisible Architects Transforming Reactants into Products

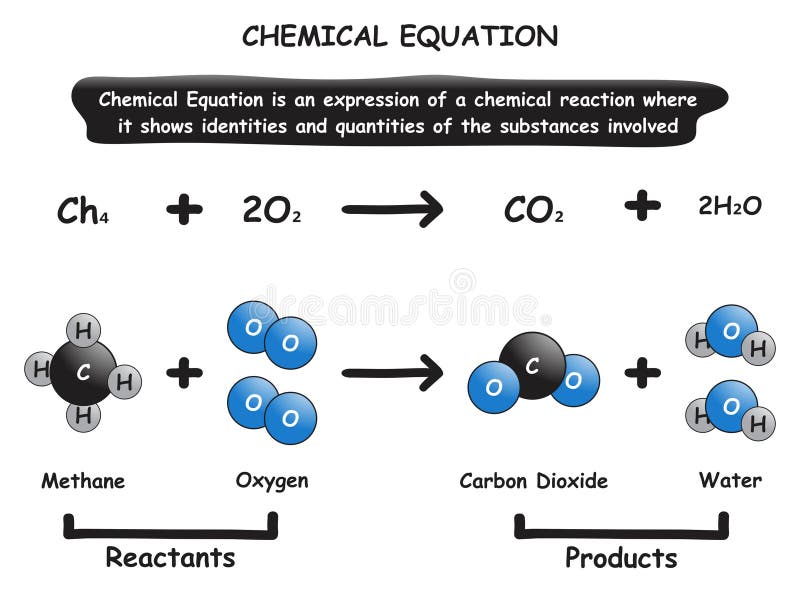

In the silent heartbeat of chemical transformations, catalysts play a pivotal yet often underappreciated role—speeding up reactions without being consumed, merging reactants with precision to form new, valuable products. This dynamic process underpins countless industrial, biological, and technological applications, turning raw starting materials into elegant solutions, fuels, and medicines. Far more than passive facilitators, catalysts reshape molecular interactions, lowering energy barriers and enabling reactions to proceed under milder conditions—making modern chemistry efficient, sustainable, and scalable.

A catalyst enables chemical reactions by providing an alternative reaction pathway with a lower activation energy. In essence, it doesn’t create new substances but lowers the energetic hurdle that reactants must overcome to join and transform. This principle lies at the core of industrial chemistry.

Take the Haber-Bosch process, where iron catalysts facilitate the direct synthesis of ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen—reaction conditions once deemed impractical now form the backbone of global fertilizer production. “Without catalysts, many essential chemical transformations would occur too slowly or require extreme temperatures and pressures,” stated Dr. Elena Morozova, a chemical engineer specializing in catalytic processes at the Institute for Catalytic Innovation.

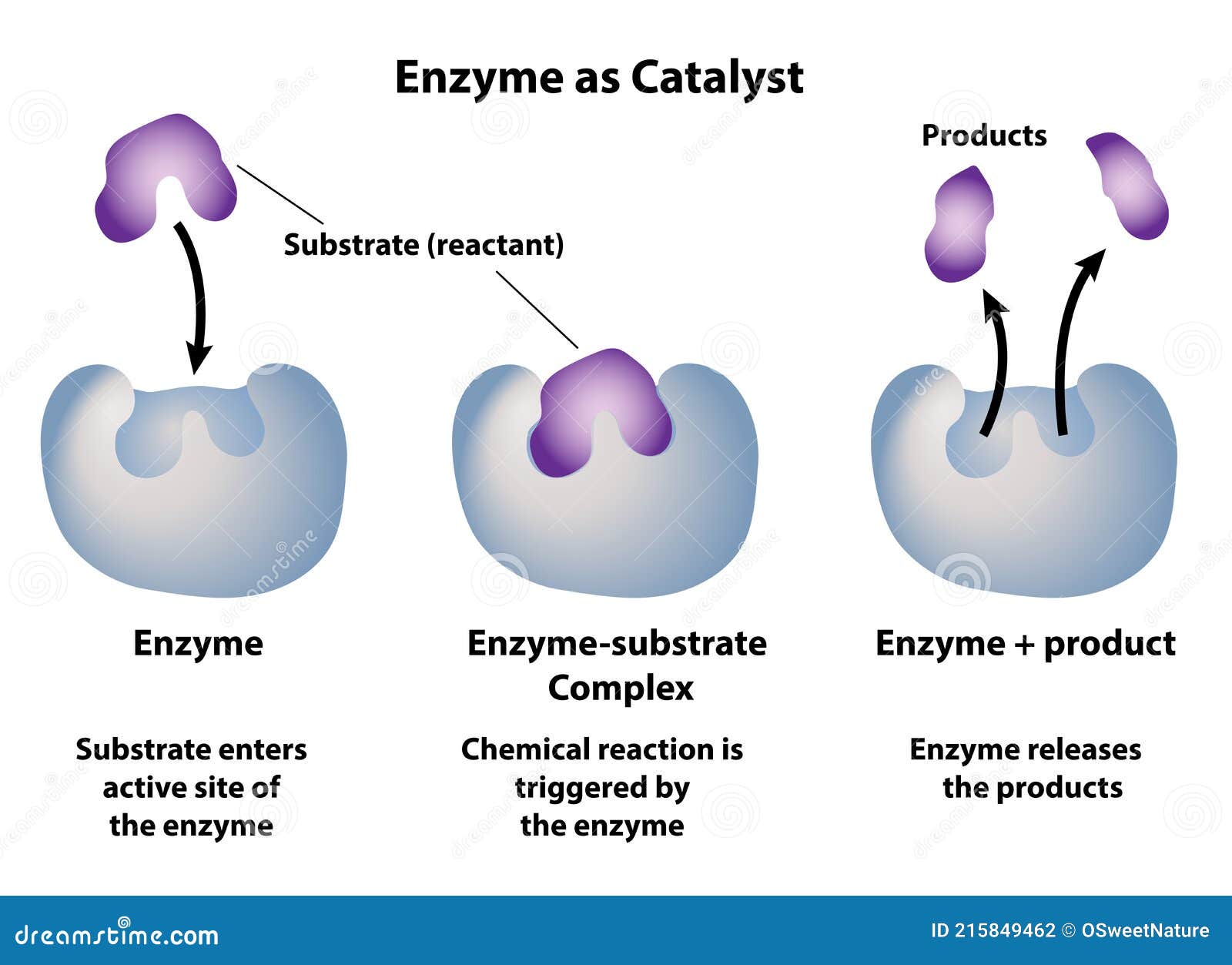

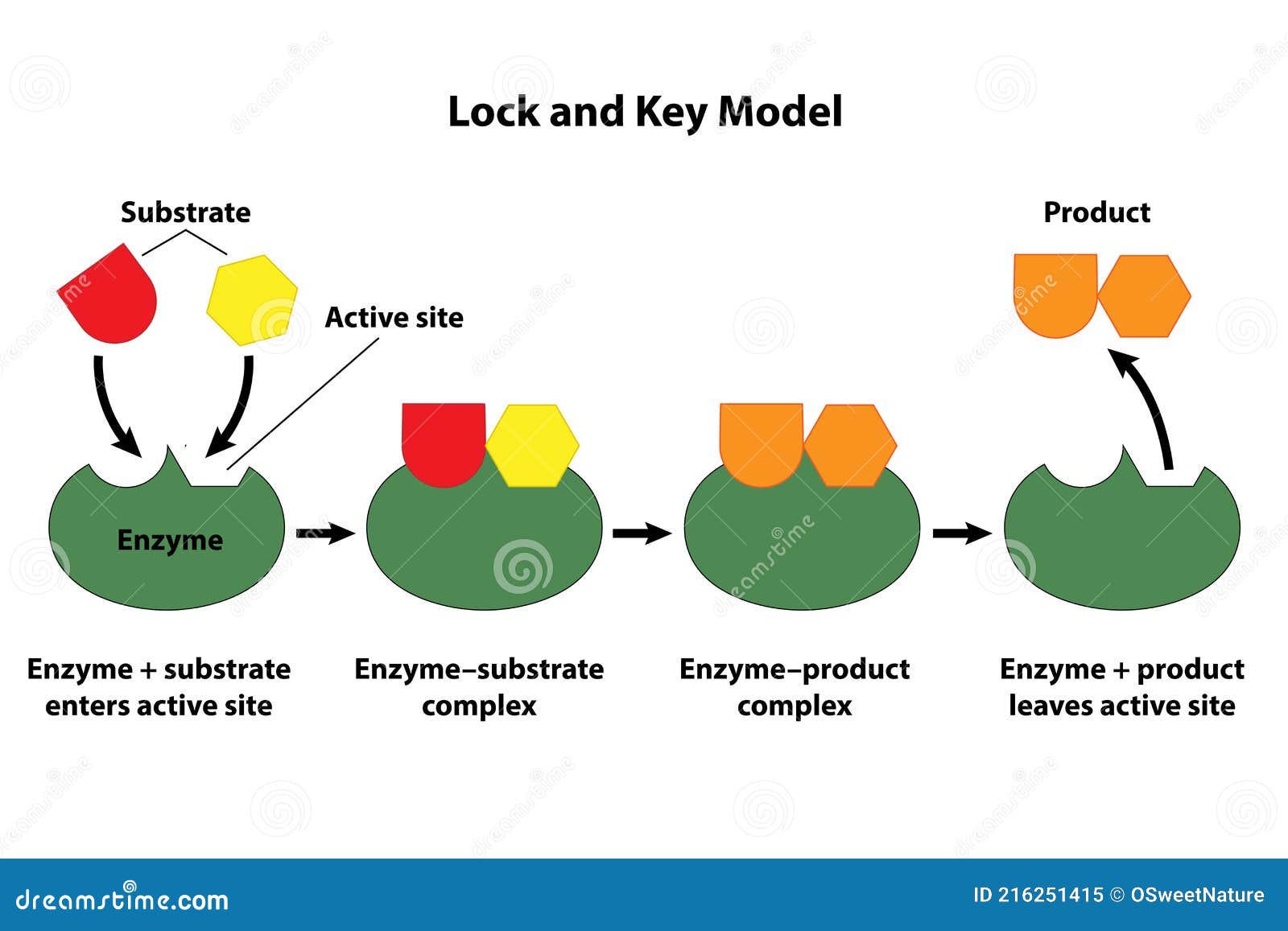

“They make the impossible practically possible.” Keys to catalytic efficiency lie in their unique interaction with reactants. Most catalysts do not bind permanently but enable transient yet critical molecular orientations and electron transfers. In enzymatic catalysis—nature’s masterful use of catalysts—proteins act as highly selective molecular scaffolds.

Each enzyme’s active site precisely holds substrates, stabilizing transition states and steering reactions toward specific products. “Enzymes demonstrate exquisite selectivity,” notes Dr. Amir Chen, a biochemist at the BioDiese Research Institute.

“They don’t just speed up reactions—they determine the exact molecules that form.” This specificity reduced to a series of chemical fingerprints, guiding industrial biocatalysts toward greener, more targeted synthesis. Catalysts operate across three primary domains: homogeneous, heterogeneous, and enzymatic. Homogeneous catalysts, dissolved in the same phase as reactants, excel in precision—capable of low-temperature reactions and controlled stereochemistry.

Transition metal complexes, often ligated with organic co-catalysts, dominate pharmaceutical and fine chemical manufacturing. Heterogeneous catalysts, solid surfaces like platinum or alumina, provide rugged stability and recyclability, making them indispensable in automotive catalytic converters and petroleum refining. “Heterogeneous catalysts protect against catalyst degradation,” explains Dr.

Lin Wei, a materials scientist at the Catalysis Center for Energy Solutions. “Their surface structure influences what products emerge—making them key to controlling reaction selectivity.” Beyond industrial applications, catalytic recycling of reactants is revolutionizing sustainability efforts. Heterogeneous catalysts convert carbon dioxide and methane into syngas—essentially rewiring greenhouse gases into feedstocks.

“This isn’t just chemistry; it’s chemistry as carbon management,” asserts Dr. Clara Strauss, a leader in green catalysis at the Global Institute for Clean Chemistry. “By enabling energy-efficient transformations with renewably derived inputs, catalysts offer a practical path to circular economies.” Yet, despite their transformative power, challenges persist.

Catalyst deactivation—from poisoning by impurities or sintering at high temperatures—remains a critical bottleneck. Researchers are responding with innovations like self-healing metal alloys and nanoengineered surfaces that maintain activity over longer cycles. “Stability under real-world conditions defines success,” notes Dr.

Wei. “A catalyst might work perfectly in a lab, but if it loses function within hours in industry, it serves no practical purpose.” In biological systems, catalysts operate at awe-inspiring efficiency—sometimes accelerating reactions by up to a trillionfold. Stoichiometric ratios and molecular conformational changes fine-tune enzyme function, ensuring cellular chemistry runs with minimal waste.

This efficiency mirrors industrial goals: crafting smarter, less energy-heavy processes that reduce environmental impact. Catalysts are the invisible linchpins of chemical transformation—unseen, indispensable, yet central to progress. From the ammonia in our fertilizers to the life-saving drugs in our pharmacies, catalysts enable products that define modern life.

As research advances—directing catalytic power toward clean energy and carbon capture—the chemistry of catalysis continues to evolve, not just enabling reactions, but reshaping a sustainable future, atom by atom.

Related Post

Help I Accidentally Summoned A Lemon: Navigating the Unforeseen Realities of Spontaneous Citrus Manifestation

From Humble Beginnings to Hollywood Queen: The Life and Career of Sandra Bullock

The Peachjar Leak Scandal What Industry Leaders Are Hiding

Decoding the Ulta Logo: A Deep Dive into Beauty Retail's Iconic Branding