Carrying Capacity Defined: The Biological Boundary That Governs Life on Earth

Carrying Capacity Defined: The Biological Boundary That Governs Life on Earth

The carrying capacity of an ecosystem represents a fundamental biological threshold—the maximum population size that an environment can sustain indefinitely given the available resources and environmental constraints. Far more than a static number, this concept encapsulates a dynamic equilibrium shaped by food supply, water, space, predator-prey interactions, and climate stability. Understanding this definition is essential for conservation biology, wildlife management, urban planning, and addressing global environmental challenges.

At its core, carrying capacity reflects nature’s built-in regulatory mechanism: populations grow until resource limits impose irreversible restrictions, halting expansion and stabilizing populations through competition, disease, or reduced reproductive success.

Carrying capacity is not a fixed value but a fluctuating parameter shaped by both biotic and abiotic forces. In ecological terms, it refers to the environment’s ability to provide essential resources—energy, nutrients, shelter—and maintain conditions conducive to sustained survival and reproduction.

Ecologist Garrett Hardin, in his seminal 1968 essay “The Tragedy of the Commons,” famously illustrated the concept through a livestock grazing analogy: without regulated access, herds exceed pasture carrying capacity, triggering overuse and ecosystem degradation. “However much the environment can support, unlimited use leads to collapse,” Hardin argued. Modern ecological research confirms that carrying capacity depends on intricate feedback loops—resource availability affects population size, which in turn alters resource consumption and stress levels.

Biological Mechanisms Regulating Carrying Capacity

The biological regulation of carrying capacity unfolds across multiple levels, from individual physiology to entire community dynamics. At the individual level, access to food, water, and shelter directly influences survival and reproductive fitness. Malnourished or water-stressed organisms exhibit reduced fertility and higher mortality, acting as natural crowd control.For example, desert biomes exhibit low carrying capacity due to acute water scarcity, limiting mammal and bird populations despite abundant foraging opportunities. Ecological communities respond to resource availability through density-dependent processes—factors intensified as population density rises. Competition for limited food intensifies among conspecifics and interspecifics, often leading to behavioral shifts, territorial disputes, or migration.

Disease also plays a critical role; high population density accelerates pathogen transmission, as seen in outbreaks of myxomatosis in Australian rabbit populations or white-nose syndrome in North American bats. Predators further modulate carrying capacity by exerting top-down control—limiting prey populations through predation pressure, thereby preventing unchecked growth. Beyond individual interactions, abiotic conditions define the physical limits of carrying capacity.

Temperature extremes, seasonal variability, soil quality, and precipitation patterns shape resource predictability and abundance. Tropical rainforests support high carrying capacity for diverse species due to year-round productivity, whereas tundra ecosystems sustain only sparse populations constrained by extreme cold and permafrost.

Water availability, in particular, stands as a critical determinant across biomes.

In savannas, seasonal droughts restrict herbivore numbers, while riverine systems maintain higher biodiversity through reliable hydration and nutrient cycling. Human-induced changes—such as deforestation, freshwater extraction, and climate warming—alter these natural balances, effectively reducing ecosystem carrying capacity and increasing species vulnerability.

Carrying Capacity in Human Systems: Lessons from Urbanization and Agriculture

Human societies, though often perceived as transcending biological constraints, remain deeply subject to carrying capacity limits—especially in rapidly expanding urban centers and intensively farmed landscapes.Urban ecosystems redefine carrying capacity through infrastructure, waste management, and altered resource distribution. Cities amplify population density far beyond natural ecological norms, demanding engineered systems to supply food, water, energy, and sanitation. “A city’s true carrying capacity isn’t just people—it’s the sustainability of its life-support systems,” explains urban ecologist Timothy Beatley.

Overreliance on external inputs (like imported food or fossil fuels) masks ecological thresholds, risking resource depletion and social instability when supply chains falter. Agricultural systems further illustrate the tension between human population demands and ecological carrying capacity. The Green Revolution boosted food production dramatically, yet soil degradation, water over-extraction, and chemical runoff threaten long-term viability.

Industrial monocultures maximize short-term yields but diminish biodiversity and resilience, narrowing effective carrying capacity for future generations. In contrast, agroecological approaches mimic natural nutrient cycles and promote polyculture diversity, enhancing sustainable productivity amid environmental change.

Even global population trends reflect the invisible hand of carrying capacity.

Demographers model sustainable population densities based on resource flux, energy flows, and waste assimilation—metrics directly tied to biological limits. The challenge lies not in absolute limits, but in reconfiguring consumption patterns, technological innovation, and policy frameworks to align human development with Earth’s regenerative capacity.

The Science of Monitoring and Managing Carrying Capacity

Effective management of carrying capacity relies on rigorous ecological monitoring and adaptive strategies.Remote sensing technologies, including satellite imagery and LiDAR, now enable real-time tracking of vegetation health, land cover change, and water availability across vast landscapes. These tools help assess whether ecosystems approach their biological thresholds, guiding decisions on grazing limits, protected area boundaries, or urban expansion policies. Ecologists use population models—such as the logistic growth equation (dN/dt = rN(1 – N/K))—to estimate carrying capacity (K) under varying conditions.

“Carrying capacity is not a single number but a range dependent on resource dynamics, climate, and species interactions,” notes Dr. Sarah Johnson, a wildlife population modeler at the University of California. She emphasizes integrating field data with predictive algorithms to refine estimates amid environmental variability.

Conservation strategies, including habitat restoration, wildlife corridors, and sustainable resource use, aim to preserve ecosystem integrity and extend carrying capacity. For example, reintroducing apex predators like wolves into Yellowstone restored balanced trophic cascades, enhancing vegetation resilience and supporting broader biodiversity. Community-based management—engaging local stakeholders in sustainable hunting, irrigation, or reforestation—also strengthens human adaptation to ecological limits.

Carrying Capacity and the Future of Sustainability

As climate change accelerates and global populations approach 8 billion, the biological definition of carrying capacity gains urgent relevance. It is no longer a theoretical concept but a practical benchmark for resilience. Rising temperatures, extreme weather, and shifting precipitation patterns continually recalibrate ecosystem thresholds,

Related Post

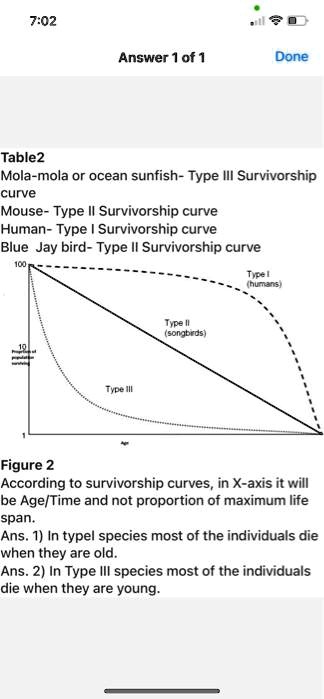

Decoding Life and Death in Nature: The Type Iii Survivorship Curve Explained

What Were Poodles Bred For? The Elite Hunting Dog’s Reason Behind the Curls

Uncensored Manhwa: A Closer Look At The Bold World Of Korean Comics

Marc Ross NFL Bio Wiki Age Height Wife Giants Salary and Net Worth