Aerobic Respiration vs Fermentation: The Invisible Engine of Energy in Every Cell

Aerobic Respiration vs Fermentation: The Invisible Engine of Energy in Every Cell

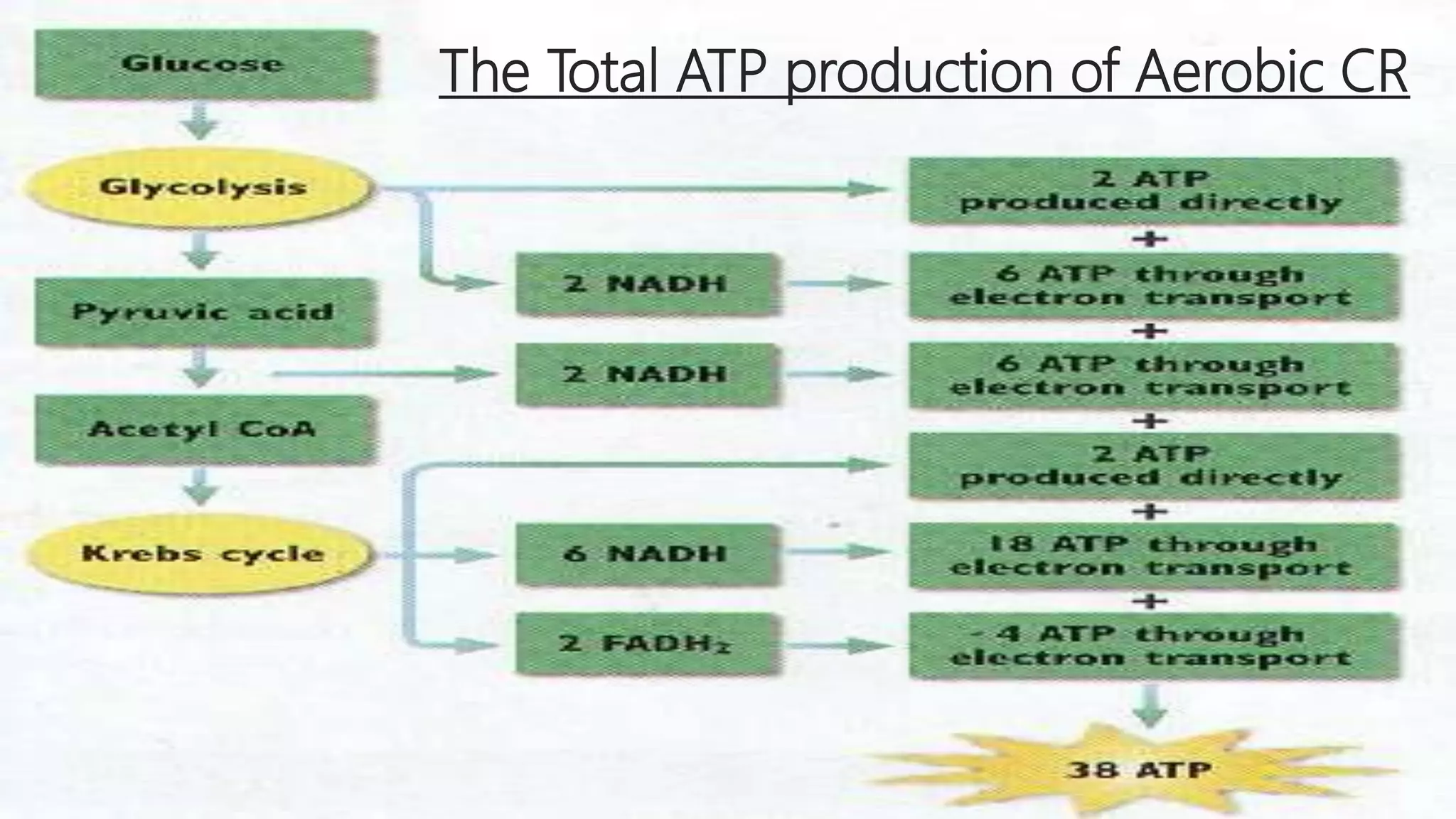

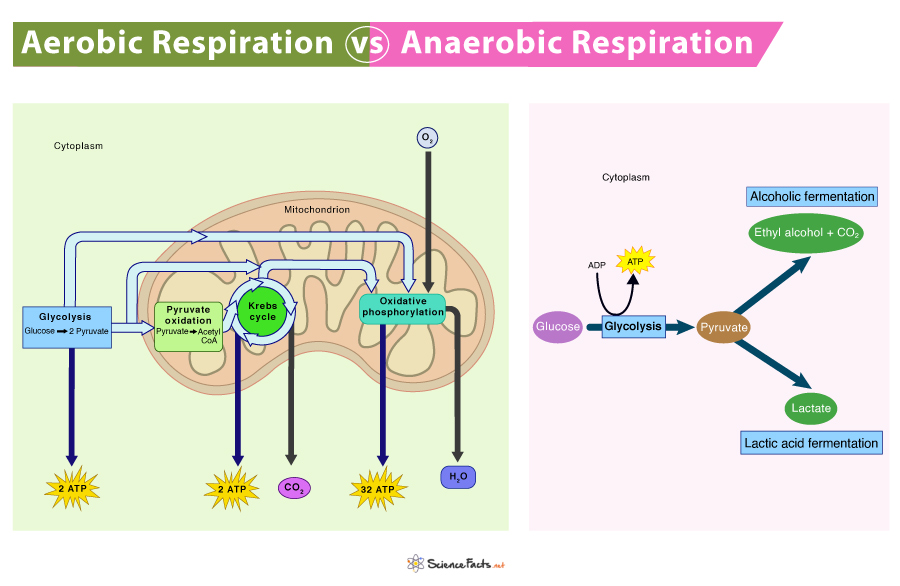

In the bustling world of cellular biology, two fundamental biochemical pathways— aerobic respiration and fermentation—dictate how life converts nutrients into usable energy. While both processes harness chemical reactions to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), their mechanisms, efficiency, and biological roles diverge dramatically. Aerobic respiration, fueled by oxygen, delivers up to 36–38 ATP molecules per glucose molecule, making it the powerhouse of metazoan and many microbial life forms.

Fermentation, in contrast, operates in the absence of oxygen, yielding only 2 net ATP per glucose but enabling survival in harsh, oxygen-deprived environments. Understanding their differences unveils the remarkable adaptability of life under varying metabolic conditions.

Core Mechanisms: Oxygen’s Role and Electron Transport

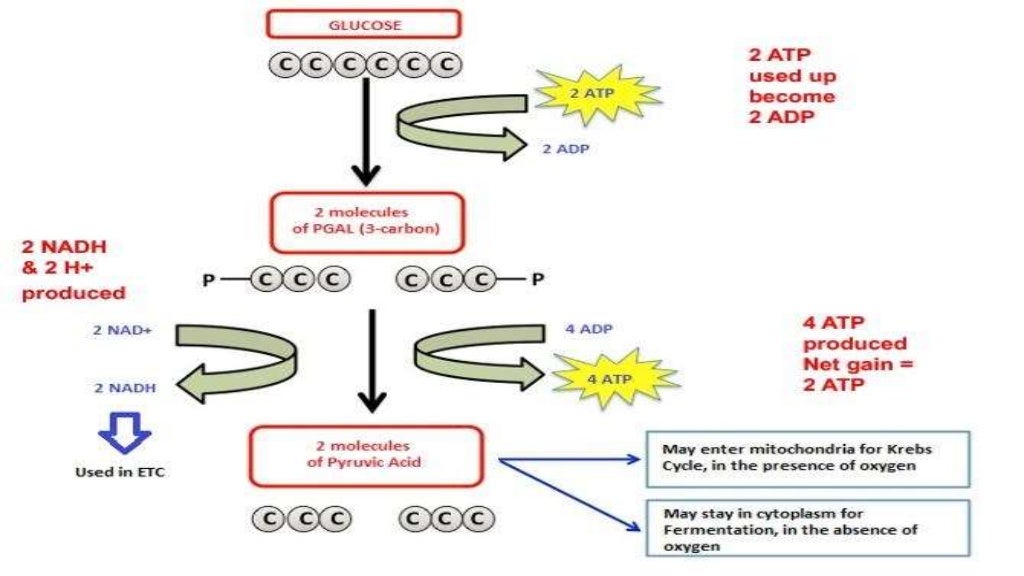

At the heart of aerobic respiration lies a sophisticated, oxygen-dependent sequence involving glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, and the electron transport chain (ETC).This aerobic process begins in the cytoplasm, where glycolysis breaks down glucose into pyruvate, producing 2 ATP and reducing equivalents in the form of NADH. The pyruvate then enters the mitochondria, where it is fully oxidized in the Krebs cycle, generating more NADH and FADH₂. These electron carriers shuttle high-energy electrons to the ETC embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane, driving proton pumping and establishing a gradient that powers ATP synthase—an intricate molecular machine that generates 30–32 ATP.

“Oxygen acts not merely as an endpoint but as a critical final acceptor, enabling the efficient extraction of energy locked within glucose,” explains biochemist Dr. Elena Torres. In stark contrast, fermentation bypasses the mitochondrial ATP factories entirely.

It relies solely on glycolysis, producing 2 ATP and regenerating NAD⁺ by converting pyruvate into lactate (lactic acid fermentation) or ethanol and CO₂ (alcoholic fermentation). Without oxygen, the electron transport chain stalls, forcing cells to recycle NADH through endogenous measures. “Fermentation is a metabolic failsafe,” notes Dr.

Rajiv Mehta, microbial physiologist. “It allows cells to sustain minimal ATP production when oxygen is scarce—critical for muscle cells during intense exercise or microbes in sediment.”

Energy Yield: Efficiency as a Functional Divide

The disparity in energy output is most stark: aerobic respiration generates 15–19 times more ATP per glucose molecule than fermentation. This difference stems from the mitochondrial ETC’s unique capacity to harness redox potential across electron carriers.Each NADH feeds into multiple ATP synthases, whereas fermentation recycles NAD⁺ through simple, low-yield chemical shifts. | Process | ATP Yield per Glucose | Key Input | Waste/Byproduct | |------------------------|-----------------------|-------------------|------------------------------| | Aerobic Respiration | 30–38 ATP | Oxygen, glucose | CO₂, H₂O | | Fermentation | 2 ATP | None (except glucose & pyruvate) | Lactate, Ethanol, CO₂ | This efficiency gap explains why aerobic metabolism dominates in complex organisms like humans, while fermentation sustains short bursts of activity in cells with intermittent oxygen access—highlighting evolution’s optimization of energy yield under environmental constraints.

Byproducts and Cellular Adaptability

Fermentation’s hallmark is its byproduct production—lactate in animal muscle cells, ethanol and CO₂ in yeast.While toxic in high concentrations, these metabolites serve vital roles. “Lactic acid accumulation triggers fatigue signals but also signals tissue damage—balancing survival and warning,” observes Dr. Torres.

In environmental microbiology, fermentation fuels anaerobic digestion, converting organic waste into biogas. Conversely, aerobic respiration generates clean metabolic exit products (CO₂ and H₂O), optimizing resource use without waste buildup. Fermentation enables cells to colonize extreme niches: deep ocean sediments, waterlogged soils, and even the human gut.

“These organisms thrive where oxygen is a luxury, not a requirement,” says Mehta, “Fermentation unlocks energy when conventional pathways are unavailable.”

Biological and Industrial Impact: From Muscle to Microbes

Human physiology exemplifies the metabolic divide: during intense exercise, rapidly contracting muscle cells switch to lactic fermentation when oxygen delivery lags, allowing ATP production to continue briefly—even if at a steep cost of fatigue and soreness. Once oxygen returns, lactic acid is cleared, restoring efficient aerobic metabolism. In industry, fermentation drives fermentation-based technologies—from brewing and baking to pharmaceutical production of antibiotics and biofuels.Fermentation vats efficiently convert sugars into ethanol and organic acids using yeast and bacteria. Meanwhile, aerobically optimized microbes, such as engineered *Escherichia coli*, produce insulin and other biopharmaceuticals via respiration-driven systems. Microbial communities further illustrate this duality: dense biofilms alternate between aerobic respiration at outer layers and fermentation deeper within, creating metabolic microzones that enhance survival and resource exploitation.

Regulation and Evolutionary Significance

Both pathways are tightly regulated to match energy demand and environmental conditions. Aerobic respiration responds to ATP/ADP ratios via enzymes like phosphofructokinase, which slows glycolysis when energy is plentiful. Fermentation, activated under hypoxia, upregulates key enzymes (e.g., lactate dehydrogenase) to

Related Post

Laura Lee Net Worth and Earnings

Josh Duggar News 2024: What’s Unfolding – A New Era of Influence and Activism

How Many Ounces in a Water Bottle? The Complete Guide to Bottle Sizes Explained

Are Basil Leaves The Same As Bay Leaves? The Definitive Guide to Two Culinary Standouts