Absolute vs. Comparative Advantage: Which Determines Economic Wins in Global Trade?

Absolute vs. Comparative Advantage: Which Determines Economic Wins in Global Trade?

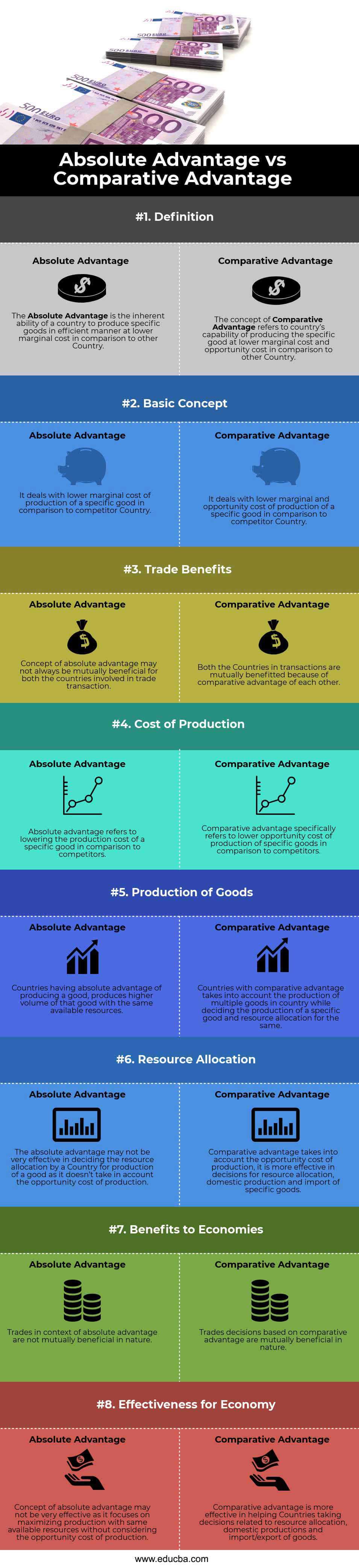

When nations engage in international commerce, two foundational economic principles—absolute advantage and comparative advantage—shape trade patterns and growth potential. While both concepts aim to explain how countries benefit from specialization, their implications differ significantly. Absolute advantage identifies which country can produce more output with the same resources; comparative advantage reveals the deeper, more nuanced gains from trade based on relative opportunity costs.

Understanding which framework better explains long-term economic efficiency and cooperative prosperity is essential in an era defined by shifting supply chains and geopolitical realignments.

Absolute advantage, a concept first articulated by Adam Smith in 1776, rests on a straightforward premise: a nation holds an absolute advantage if it produces a good using fewer resources than another country. For example, Saudi Arabia mines oil more efficiently—extracting larger volumes with lesser labor and capital—than many resource-poor nations.

This efficiency makes absolute advantage a compelling initial argument for specialization: countries should focus on what they produce most productively. Yet this view, while intuitive, misses a critical layer of economic reality. A nation may produce more of everything but still benefit less from trade if its most efficient output carries no meaningful advantage over imports.

Beyond Raw Efficiency: The Hidden Power of Comparative Advantage

The true engine of mutual growth in global trade lies in comparative advantage, a principle refined by David Ricardo in the early 19th century. Unlike absolute advantage, which centers on productivity alone, comparative advantage evaluates opportunity costs—the value of the next best alternative forgone when producing one good over another. A country enjoys comparative advantage in producing a product if its opportunity cost of output is lower than that of its trading partners, even if it lacks absolute efficiency in all sectors.This insight transforms trade theory from a zero-sum competition into a collaborative expansion of overall prosperity.

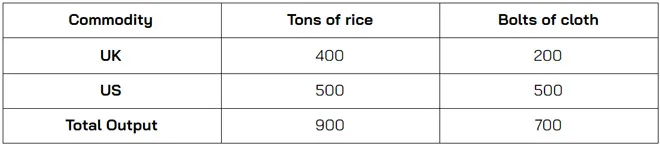

To illustrate, consider two nations: one capable of producing widgets and textiles with high efficiency, another able to grow food and textiles with comparatively lower costs in labor. Suppose Country A excels at both, but its opportunity cost of making textiles is significantly lower than Country B’s.

Meanwhile, Country B’s chance to produce textiles comes at a steeper cost. Under comparative advantage, both nations specialize—Country A focuses on textiles, Country B on food and utilizes more labor-efficient textile production—then trade. The result: total output rises, consumption improves, and both societies benefit without sacrificing self-sufficiency.

Comparative advantage thus unlocks gains invisible to absolute analysis. It recognizes that even inefficient producers can thrive through trade by leveraging relative strengths. “The secret of economic growth,” economist Paul Krugman observed, “is not merely outproducing others, but identifying and exploiting which goods its own structure—its institutions, skills, and resources—allow for least opportunity cost.”

Core Differences in Application and Real-World Impact

While absolute advantage identifies who can win in quantity, comparative advantage explains who wins in quality through specialization.Economists distinguish these by their scope and implications: - Absolute Advantage: Quantifies raw productivity; best for single-sector assessments. A nation with superior technology, land, or capital may dominate output—China’s electronic manufacturing or the U.S. agricultural sector exemplify this.

- Comparative Advantage: Focuses on trade-enabling efficiency; accounts for interdependent resource allocation across markets. It encourages diversified, balanced growth, reducing vulnerability to sector-specific shocks. Real-world examples reinforce this.

In the 20th century, Japan—lacking vast natural resources—developed a comparative advantage in high-value electronics and automotive manufacturing by excelling where opportunity costs were low. Meanwhile, Brazil cultivated agricultural dominance through lower labor costs in farming relative to industrial alternatives. These divergences highlight comparative advantage as a dynamic framework guiding policy, investment, and global integration.

Expanding on relative efficiency, economists frequently use production possibility frontiers (PPFs) to visualize trade-offs. When nations specialize according to comparative advantage, the PPF shifts outward collectively, enabling shared gains. But misapplying absolute advantage—assuming only superior output justifies trade—can lead to inefficient specialization, underutilized potential, and missed synergies.

Criticisms and Expansions: When Traditional Frameworks Face Limits

Though foundational, comparative advantage faces scrutiny in modern contexts. Critics note it assumes perfect mobility of resources, static production technologies, and ignore externalities like environmental degradation or labor standards. Global supply chains introduce complexity—intangible factors such as political stability, intellectual property rights, and infrastructure quality also shape competitive positioning.Moreover, developing economies may struggle to achieve true comparative advantage due to institutional constraints, limited technology access, or dependency on volatile commodity markets. However, these limits do not invalidate core insight—rather, they refine application. The rise of digital trade, green economies, and value-added manufacturing demands updated interpretations.

Comparative advantage now increasingly includes skills, innovation capacity, and sustainable production methods. Nations investing in education, green tech, and digital infrastructure may develop new comparative edges critical for future competitiveness. ىCallbackKey: Comparative advantage remains a vital lens, especially when paired with adaptive policy and inclusive development strategies.

As industries evolve, so too must frameworks guiding global engagement. In summary, while absolute advantage offers a clear path to productivity, comparative advantage reveals the deeper, mutually enriching logic of global trade. By focusing on relative opportunity costs, countries unlock higher output, innovation, and shared prosperity—making it the superior framework for understanding—and shaping—the future of international economic relations.

Related Post

Rhonda Walker WDIV Bio Age Height Husband Surgery Salary and Net Worth

Adopt Me! Goo: The Unforgettable Journey of Gg’s Adoption Adventures

C U Soon: The Seismic Shift Redefining Digital Engagement and Personal Connection